Not all who push for change join a protest march. Instead, some people serve as role models or educate the next generation. Others may build content for their communities, start new programs, or shatter glass ceilings.

While recent decades have seen an influx of East and South Asian professionals into computing, the field has one of the lowest rates of employment for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous peoples. This is especially true of technical specialties like engineering and programming. There is also an unfortunate hierarchy within the field. For every well-paid job at a tech company there may be half a dozen supporting roles for highly specialized contractors and vendors. This “shadow ecosystem” is less white, more female, older, and lower paid.

Meet nine talented individuals who led the way for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) contributions in computing and explore related materials from the CHM collection.

In 1951 at MIT, 18-year-old Joseph “Joe” Thompson was among the first operators of a new kind of machine: the Whirlwind computer. Started during WWII as an analog flight simulator for the Navy, Project Whirlwind benefited from an inspired form of mission creep. It grew into a pioneering, real-time, digital computer that established the model for generations of both military and business machines to come.

MIT recruited Thompson for college, and his job running and programming Whirlwind at night introduced him to computing and supported him as a college student.

Thompson was the first Black employee in Whirlwind’s early years. He was also one of the few Black employees at RAND corporation, where he helped program Whirlwind’s direct successor, the continent-spanning SAGE early warning system for nuclear attacks. SAGE helped pioneer computer networking, interactive computing, and large-scale software development.

Earning greater responsibility at RAND and other companies throughout his career, Thompson eventually retired as a branch head. Outside of work, he found time to mentor teens in troubled schools, encouraging them to continue their education.

In 1968, Lois Jennings cofounded the iconic Whole Earth Catalog: Access to Tools with her then-husband, counterculture legend Stewart Brand. It was a loose collection of ideas and practical techniques that inspired a generation of hippies and computing pioneers.

Jennings’ first job after college was as a “hidden figure” doing calculations for the Navy, both manually and with computers.

Jennings met Brand while he was attending the National Congress of American Indians, exploring his interest in Native culture. Their tumultuous marriage lasted through the peak of the Catalog years.

The Catalog’s guiding principle was “coevolution,” the idea that human culture evolves in step with its tools. Jennings and Brand had been exposed to Douglas Engelbart’s futuristic computing lab, and they believed that computers might become the most flexible tools of all.

Jennings was a founding director and treasurer of the People’s Computer Company, an offshoot of the Catalog community that helped inspire personal computing. She later married Keith Britton, and they were both involved in the Homebrew Computer Club, a group of hippie hackers and small computer enthusiasts whose members included the future founders of Apple.

Growing up in Piedras Negras, a Mexican border town, Hector Ruiz aspired to open an auto repair shop. But, when he was thirteen, American missionary Olive Givin suggested he instead attend high school on the US side of the border, and she offered to pay his first year’s tuition. Ruiz went on to become CEO of a top company in another country and sue the world’s biggest manufacturer of computer chips.

A brilliant student, Ruiz was ahead of his classmates in subjects like math and chemistry, which Mexican schools taught early, but he was behind in English. With mentoring from his teachers, however, he graduated as class valedictorian. That brought an automatic scholarship to the University of Texas at Austin, where Ruiz majored in electrical engineering and continued on to earn a doctorate at Rice.

Ruiz began his career in the semiconductor industry and discovered that he had a talent for solving tricky manufacturing problems and for management. He rose steadily through the ranks at Texas Instruments and Motorola and was then recruited to be the heir apparent to the CEO of ailing chipmaker AMD. He accepted the offer.

While AMD’s chips were often superior, the smaller company was being strangled by Intel’s monopolistic practices. When Ruiz became CEO, he sued Intel and won. He then spun off much of AMD’s manufacturing to a new foundry, in partnership with a Middle Eastern prince.

When Stanford PhD student Marc Hannah met his doctoral advisor, Jim Clark, he never dreamed he would help design a chip that would revolutionize computing. Their Geometry Engine made possible the astonishingly realistic imagery in the popular movies Jurassic Park and Terminator 2 and launched the wildly successful Silicon Graphics Inc. (SGI). The chip’s offshoots are essential to modern AI and “big data.”

Hannah grew up near Chicago and was recruited to the Illinois Institute of Technology through a Bell Labs scholarship program for talented minority students. He went on to Stanford, where he became interested in graphics and was introduced to Jim Clark. Clark recruited Hannah and several other students to cofound Silicon Graphics with him.

Hannah had helped Clark with the first Geometry Engine at Stanford, and at Silicon Graphics he took over the design of the second generation of the chip, the core technology of the company’s graphics terminals and workstations. He eventually became a vice president and chief scientist.

The Geometry Engine established the niche for graphics coprocessors, specialized chips that run alongside CPUs to handle the heavy math needed to manipulate images. Descendants are today found in nearly every smartphone and computer, where they speed up repetitive calculations from graphics to deep learning.

After leaving SGI, Hannah worked for or started several technology ventures, including NVidia. He is a partner in the Strategic Urban Development Alliance (SUDA), a real estate company that seeks to make a positive difference in low-income areas.

Watch Marc Hannah’s full oral history video or read the transcript.

P.S. CHM owes a special debt to Clark, Hannah, and their cofounders. The Museum’s main building was part of the original SGI campus!

Mitch Kapor hoped to create a new, progressive kind of company at the heart of the computer industry. In 1982, that wasn’t Silicon Valley but greater Boston. Kapor and cofounder Jonathan Sachs developed Lotus 1-2-3, an improved version of the pioneering spreadsheet software VisiCalc. Riding the explosive growth of the new personal computer industry, the company was an instant powerhouse, with $53 million in sales its first year.

Since the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a few American companies had begun efforts to become more diverse. Among tech firms, Boston minicomputer pioneer Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) was a leader, with its company-wide Valuing Differences training seminars and hiring practices.

But Kapor wanted to go farther at Lotus and create “. . . a 1980s company with 1960s values.” He hired Freada Klein as director of employee relations, organizational development, and management training. She had previously cofounded the first group to address sexual harassment in the US. With Kapor’s backing as CEO, Klein helped shape a set of policies that established accountability, including diversity.

This sort of tie to compensation remains rare today. Klein also helped create an ombuds function and a diversity council, and she made Lotus the first tech firm to sponsor an AIDS walk when the disease was highly stigmatized.

Klein went on to consult on diversity to a wide range of corporate clients as well as on the Civil Rights Act of 1991. She and Kapor married long after they had left Lotus, and their venture firm and foundation support a variety of diversity, inclusion, and education efforts, including the new oral histories featured in this story. Klein emphasizes the importance of laying the groundwork for diversity and inclusion early in a company’s development. She says, “If you’ve already built a company that isn’t diverse and now, how do you retrofit it? How do you turn the Titanic around?”

Watch the full Freada Kapor Klein and Mitch Kapor oral history video or read the transcript.

Read Mitch Kapor’s 2008 oral history transcript.

In the late 1980s, lawyer and artist Kamal Al Mansour set out to bring pan-African culture to the digital realm. He started with CPTime Clip Art, the first major disk of Afrocentric imagery for personal computers. The title wryly reclaimed the expression “Colored people’s time,” a stereotype that Black people are always running late. For Al Mansour it became a personal call to action: “It’s our time, it’s time for people of color to be online, to be digital.” He also started a dial-up service for research and messaging called CPTime On-Line.

Growing up in Los Angeles, Al Mansour had little interest in computing. He majored in political science at UCLA and then went on to UC Hastings law school Law in San Francisco. His first job was at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory handling contracts and intellectual property related to NASA’s rockets. That sparked an interest in technology, where he discovered how little room there was in the field for Blacks or their culture.

After his television epiphany, Al Mansour made it his mission to change things with CPTime Clip Art. His follow-up program, Who We Are, included hundreds of questions and answers about Black civilizations. He soon had a catalog of titles addressing a variety of topics, including diseases affecting people of African descent and a program that sought to raise the self-esteem of Black youth. His materials were being bought by school districts and universities and were covered in major print and TV media.

As bigger organizations like NetNoir began to provide Afrocentric content for the exploding online world, Al Mansour chose not to follow. He instead became a full-time artist, working with both Afrocentric and universal themes.

When he was hired by Lettie McGuire, Sean O’Connor knew it was more than a job. Together, the two of them created a major portion of the Afrocentric net and helped to bring many others online as pioneering web designers.

McGuire had just been made Art Director and programmer of NetNoir, billed as “the soul of cyberspace.” The cofounders, David Ellington and Malcolm CasSelle, handled the business end and left much of the content to McGuire and O’Connor. They decided which celebrities to interview, what features to add, and were responsible for coding the site itself. At its height, NetNoir was the most vibrant Afrocentric community online, with Motown Records and Vibe magazine contributing to the music section, Olympic gold medalist Carl Lewis writing on sports, and a range of interactive forums with celebrities. McGuire and O’Connor wrote spotlights like “Technology Month” and “Black History Month.”

NetNoir started on AOL, which gave it social features that were not common on the web for another decade. McGuire and O’Connor had to become experts in AOL’s own page design language, RainMan. But NetNoir’s web presence was also growing under McGuire’s direction, and there was plenty of opportunity to break new ground in web design.

By the late 1990s, NetNoir, GoAfro on CompuServe, and other dedicated Afrocentric sites were fading, along with the first wave of online communities overall. The communal roles of the pioneering Afrocentric sites would be inherited by content creators within mass social media, and even later by Black Twitter. McGuire and O’Connor continued their careers as top web designers and went on to launch some of the first technology centers for BIPOC youth—O’Connor in Jamaica and McGuire in San Francisco and Harlem.

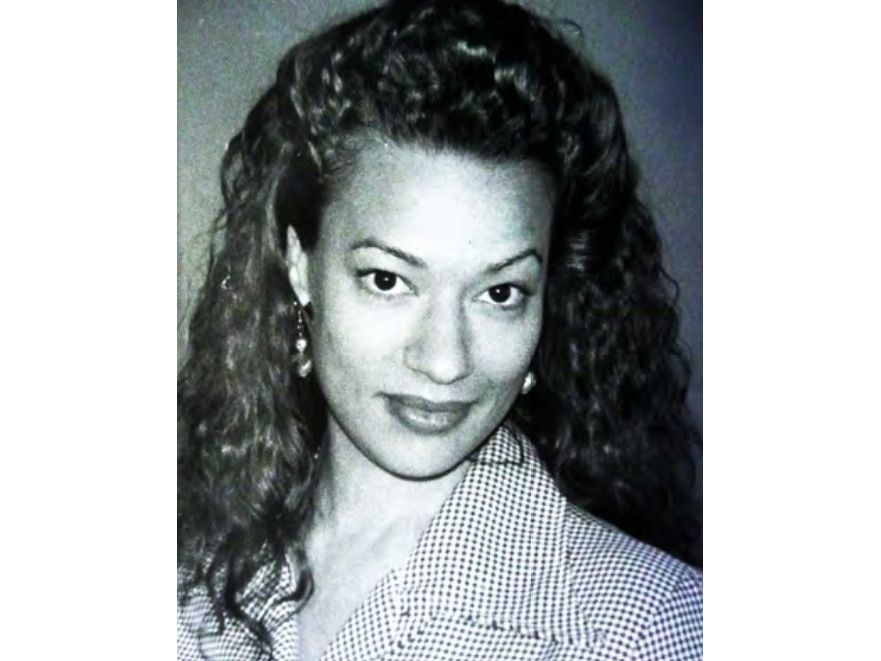

Lettie McGuire, staff photo for NetNoir, 1990s.

Visit the collection to read Lettie McGuire’s Personal Account.

Watch Sean O’Connor’s full oral history video or read the transcript.

This story was supported by a generous grant from the Kapor Center, along with five related events and a series of ten oral histories with BIPOC computing pioneers. Please suggest candidates for future oral histories!