Over the past five decades, the venture capital industry has become a notable force in fueling the start-up, growth, and impact of many innovative tech companies that have changed the world. Though the majority of startups do not receive funding from venture capitalists, in Silicon Valley they have invested in and helped launch and grow companies like Intel, Apple, Google and Uber, profoundly changing how billions of people live, work, and play.

Venture capitalists help determine what new tech products and services become a part of our lives. Understanding how the venture capital industry works, how it has developed, and where it’s headed provides context in which to evaluate the benefits and downsides of tech innovations and the companies that create them.

Voices of venture capital in their own words.

Venture capitalists, or “VCs”, fund startup companies. They raise money from limited partners—often investors representing pension funds, insurance companies, endowments, foundations, and wealthy people—to provide money to entrepreneurs. In exchange, VCs get part ownership through stock and also a seat on the board. They advise the CEO and foster connections to help the new business find customers, suppliers, executives, and employees.

New tech companies are risky bets. Venture capitalists expect most of those they’ve invested in to fail or break even but hope at least a few will pay off, either through sale to another company or by going public in the stock market with an IPO (initial public offering).

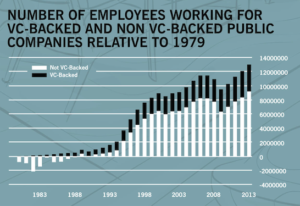

Image credit: “How Much Does Venture Capital Drive the U.S. Economy?” Ilya A. Strebulaev and Will Gornall, Insights by Stanford Business, Oct. 21, 2015.

Many argue that the US’s global domination in tech could not have happened without these pioneering investors and point out how companies funded by venture capital employ hundreds of thousands of people, some lifted out of poverty. Others believe their impact has been overstated, that “picking winners” perpetuates inequality and prevents healthy competition, or that VCs focus more on enriching themselves and their partners than on building lasting companies and creating jobs.

What do you think? Explore stories of venture capitalists in their own words.

In those days if you said you were a venture capitalist people didn’t understand—including your wife—what you did for a living.

— Peter Crisp, Venrock

Early investors in new businesses tended to be from wealthy families dabbling in things that interested them. After World War II, a growing pool of people who wanted to make new technologies broadly available through new companies began to experiment with partnership and funding models, learned how to find promising entrepreneurs, and banded together to lobby for favorable investment policies. Meet some people from the formative days of venture investing in the timeline below.

How do venture capitalists see their roles as funders, board members, and advisors?

|

|

“The role of the general partner in this play was to be the absolute best director that the entrepreneur had, and that if you could win the Oscar, if you will, for the best supporting actor, that that would be a very fine goal.” —Henry McCance, Greylock

|

|

“So, I’m not a technologist, but I am a pretty good judge of people and in business it’s all about people. If the people are right, the business has a chance. If they’re wrong, it won’t work. So, the most critical part of that process is evaluating people.” —Frank Bonsal, NEA

|

|

|

|

“Leah’s [Busque, founder of TaskRabbit] a truth seeker, right? And I’m a truth seeker. And so, we have mutual respect for the truth. And what that means is, as long as she’s seeking truth and I’m seeking truth, we can have an honest discussion about things.” —Ann Miura-Ko, Floodgate

|

|

“Being a venture capitalist is a staff position. You’re trying to get people to do things but you don’t have a lot of direct authority. You can fire them ultimately but that’s a very tough thing to do. You can’t do it too often. So you really have to earn people’s respect and get them to want to do things that they should do.” —Bill Davidow, Mohr Davidow Ventures

|

|

What do venture capitalists’ relationships with entrepreneurs look like?

The word cloud below was created from a collection of phrases that thirty venture capitalists used to describe how they see their relationship with entrepreneurs in their oral histories at CHM. It gives greater prominence to words that appeared more frequently. Unsurprisingly, almost every venture capitalist used the words “entrepreneur,” “company” and “people.” But the words that only one or a few of them used reveal several different, sometimes opposite approaches to the founder-funder dynamic. For example, words like “consensus” and “debate,” or “reasoned” and “feel,” indicate different approaches to advising.

Many factors come into play when a funder considers whether or not to found a new startup. Decisions are based on facts like the experience of the founders and whether a new product actually works, as well as more subjective factors like first impressions, unconscious bias, and “gut feel.” Relationships and networks also play a key role. The funding stories of early startup Intel in 1968 and Apple almost a decade later presents a study in contrasts, although both have a happy ending.

Robert Noyce was an MIT graduate, a brilliant physicist, and a natural leader. He was originally recruited by William Shockley to join Shockley labs in 1956, an early semiconductor company. Less than two years later, along with 7 colleagues, Noyce left Shockley to form Fairchild Semiconductor. After serving in several senior management positions at Fairchild, Noyce and cofounder Gordon Moore, the chemist of “Moore’s Law” fame, left to form their own company in 1968. They called it “Intel” for “integrated electronics,” but they weren’t quite sure what they wanted to make. They needed a funder who would have enough faith in them to take a chance and give them time to figure it out.

Steve “Woz” Wozniak and Steve Jobs met in 1971, and together made and sold “Blue Boxes,” illicit devices for making free long-distance calls. They formed Apple Computer in 1976, and demonstrated the Apple I Woz had built in the Jobs family garage to the hobbyists at the Homebrew Computer Club. It was a hit and the duo was inspired to form a company to sell the new personal computer to their hobbyist friends. Jobs sold his VW bus and Woz his HP calculator to fund the new business, but it wasn’t enough so they went looking for funding. Venture capitalist Don Valentine was turned off by their youth and lack of experience, long hair, beards, and “hippie” clothes. He was unwilling to take a chance on the two “renegades from the human race.” He wasn’t the only one. Apple desperately needed money to get off the ground.

Venture capitalist Arthur Rock had helped Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore and their cofounders establish Fairchild Semiconductor, and he’d stayed in touch over the years, impressed with their business acumen and technical brilliance. When Noyce called to ask if he would fund the new company, Rock immediately said, “I’m in.” Gordon Moore says, “That has to have been the easiest financing of a startup to have occurred in Silicon Valley.” To raise the $2.5 million needed, Rock typed up a vague three-paragraph business plan himself to give other investors at least something to look at.

Knowing that his friend, Mike Markkula, who had retired early from Intel, spent his spare time mentoring young entrepreneurs, Don Valentine introduced him to the two Steves. Markkula’s technical knowledge and dabbling with early computers helped him see how brilliant Woz’s product was and he agreed to come on board with an investment as a third cofounder and committed to guide the company. He wrote the business plan himself and describes why he took it on in this video. Markkula’s reputation helped venture capitalists overcome their skepticism about the other two cofounders. Indeed, their youth and inexperience was cited as a “risk factor” in the business plan.

|

Intel is the world’s most valuable semiconductor chip maker, with revenues of nearly $70 billion in 2019 and a market capitalization over $300 billion. Its microprocessors are found in most personal computers. |

|

|

Apple is the world’s most valuable publicly traded corporation at over a trillion dollars. Taking the world by storm in 2007, the company’s ubiquitous iPhone accounts for over half of its revenue. |

The venture capital industry is overwhelmingly male and white, and white male VCs tend to invest in entrepreneurs who look like themselves, something called “pattern matching.” But there have been women involved in venture capital from the beginning and there is a growing understanding, based on years of solid research, that companies with more diverse leadership in terms of gender, race, ethnicity, etc. outperform companies with less diversity.

Although 52 women became VC partners or general partners for the first time in 2019, a 37 percent increase since 2018, there is still much more to be done. Below, both women and men venture capitalists from Silicon Valley share their experiences, perspectives, and strategies.

What does venture capital look like outside Silicon Valley?

With nearly 50 percent of global investment, Silicon Valley is the undisputed capital for raising capital. But the industry has also matured on the East Coast where it originally began, with some older firms developing a bi-coastal presence. It is growing in areas like the Midwest as the role of entrepreneurial endeavors in building healthy local economies is being recognized. And around the world it’s evolving very differently in different places and flowing across borders. According to a report from the Rhodium Group, between 2009 and 2019, China invested $148 billion in the US and the US invested $276 billion in China.

Below, meet some VCs from beyond Silicon Valley.

In recent decades venture capital has generated more economic and employment growth in the US than any other investment sector, according to the Brookings Institute, delivering more than 21 percent of the country’s GDP through venture-backed business revenues though making up only .2 percent of GDP. But venture capital has also been in the news for its abysmal record on equity and access in the industry and for stifling competition by propping up companies that aren’t earning revenues, sometimes leading to layoffs and company collapse. Is the model broken? Does it no longer serve society?

Many individuals and organizations are working to make things better: to include more diverse funders and founders like the women investors at All Raise; to evaluate performance not just through financials but also by considering social and environmental impact as companies committed to a triple bottom line are doing; and, to consider ethical questions about sustainable growth and positive impact before funding a new business as some venture capital firms now undertake to do.

If these trends gain momentum, and if we improve on the US venture capital model, perhaps the industry’s experience and know-how can effect real change through new tech innovations that serve humanity and the planet on a massive scale.

That could be a bet worth taking.

Explore the resources below to learn more about the venture capital industry.

Steve Blank, “The Secret History of Silicon Valley,” CHM lecture, Nov. 20, 2008.

Brad Feld, “A Venture Capital History Perspective From Jack Tankersley,” FeldThoughts, August 2015.

Paul A. Gompers, “The Rise and Fall of Venture Capital,” Business and Economic History, 1994.

David H. Hsu & Martin Kenney, “Organizing Venture Capital: The Rise and Demise of American Research & Development Corporation, 1946–1973,” Industrial and Corporate Change, 14 (4), 579-616 (2004).

Jake Powers, “The History of Private Equity & Venture Capital,” Corporate LiveWire, February 2012.

Udayan Gupta, Done Deals: Venture Capitalists Tell Their Stories, Harvard Business Review Press, September 2000. See chapter on Lionel Pincus, “The Warburg Pincus Story.”

Dawn Levy, “Biography revisits Fred Terman’s roles in engineering, Stanford, Silicon Valley,” Stanford Report, November 2004.

Paul A. Gompers, Will Gornall, Steven N. Kaplan, and Ilya A. “How Do Venture Capitalists Make Decisions?” Journal of Financial Economics, Volume 135, Issue 1, January 2020, Pages 169-190.

William H. Janeway, “The Political and Financial Economics of Innovation,” Institute for New Economic Thinking, April 2012.

Riva-Melissa Tez, “Finance: An Industry Based on Psychology,” Medium, November 2014.

“The key to industrial capitalism: limited liability,” The Economist, December 1999.

Martin Kenney & John Zysman, “Unicorns, Cheshire cats, and the new dilemmas of entrepreneurial finance,” Venture Capital, 21:1, 35-50 (2019).

Pam Kostka, “More Women Became VC Partners Than Ever Before In 2019 But 65% of Venture Firms Still Have Zero Female Partners,” Medium, Feb. 7, 2020.

Pitchbook, The VC Female Founders Dashboard.