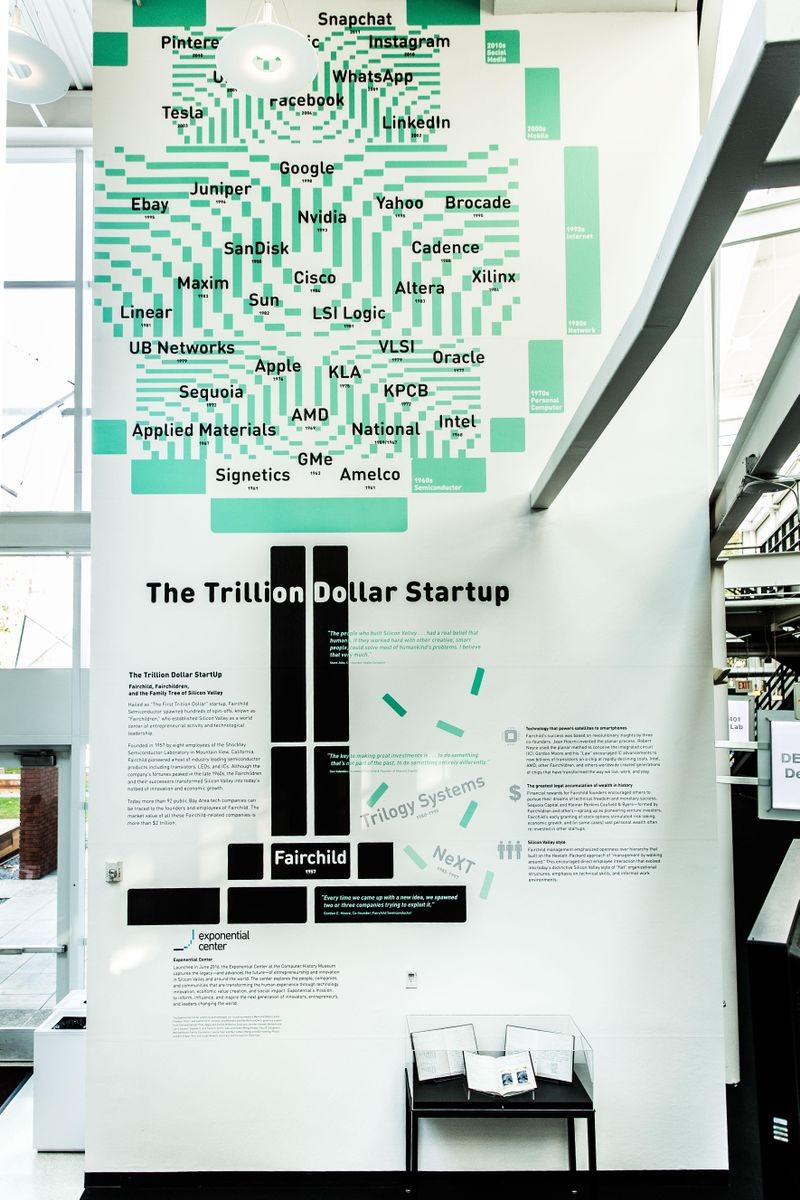

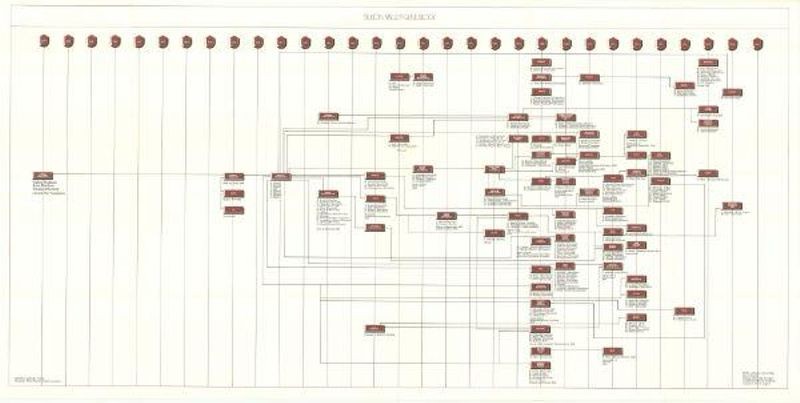

Exhibit display in CHM lobby, representing examples of the hundreds of Fairchildren established over six generations of technology ventures. Courtesy of Douglas Fairbairn Photography

Sixty years after its founding in 1957, Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation is celebrated as “The First Trillion Dollar Startup.”1 Through an unprecedented series of technical, business, and cultural innovations, the company spawned hundreds of ventures that established Silicon Valley as a world center of entrepreneurial activity and technological leadership. Although the firm’s market valuation never exceeded $2.5 billion, its surviving combined progeny have been estimated to be worth over $2 trillion.

Fairchild’s role in stimulating the explosive entrepreneurial growth of the region since the 1960s is illustrated in a new exhibit in the atrium at the Computer History Museum. Developed by the Museum’s Exponential Center, a mural display depicts the company as a giant high-tech tree, laden with a harvest of spin-off companies that span six generations of key Silicon Valley technology eras from semiconductors to social media.

Beginning early in the last century a succession of successful ventures in radio communications (Litton), microwave devices (Varian), electronic instruments (Hewlett Packard), and magnetic recording (Ampex) laid a strong foundation of entrepreneurial enterprise and technical expertise on the southern San Francisco Peninsula.

Coupled with the proximity to Stanford University, these factors attracted co-inventor of the transistor William Shockley to establish his Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory in Mountain View in 1956 to perform research into silicon semiconductor devices.

The Fairchild founders in 1961. Rear row from left: Victor Grinich, Gordon Moore, Julius Blank, Eugene Kleiner. Front row: Jay Last, Jean Hoerni, Sheldon Roberts, and Robert Noyce. Photo © Wayne Miller/Magnum Photos

Shockley’s difficult leadership style drove eight of his leading employees to defect and start their own company, Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation, in 1957. With funding from East Coast industrialist Sherman Fairchild of Fairchild Camera & Instrument Corp., the founding group developed an improved silicon transistor that found immediate application in aerospace and military defense systems.

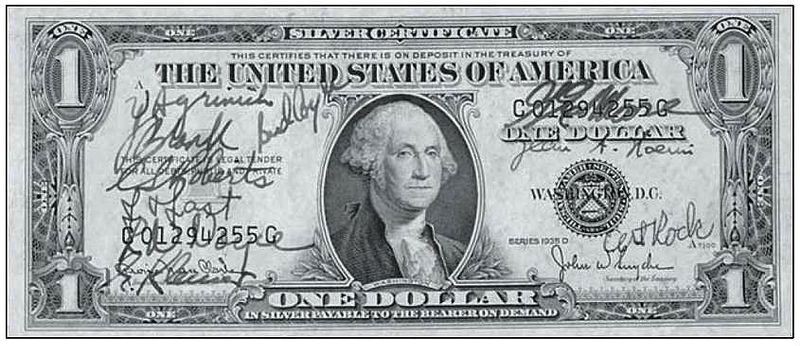

A symbolic contract signed by the Fairchild founders and bankers on September 19, 1957.

As a young New York banker, Arthur Rock helped to manage the Fairchild transaction. In 1961 he moved to San Francisco and formed Davis & Rock, one of the first notable West Coast venture capital firms. Rock later led funding of Intel and Apple.

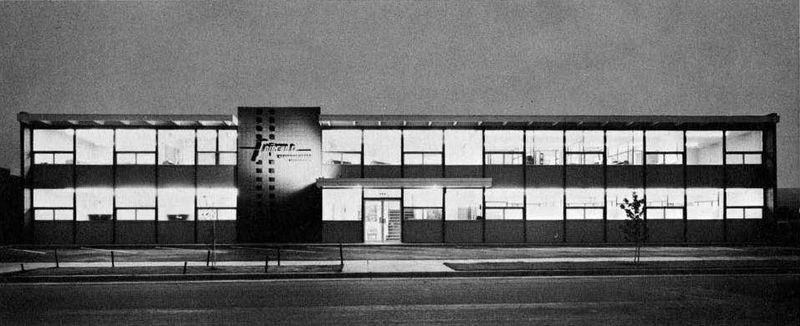

Fairchild HQ building, Charleston Avenue, Palo Alto, California (1958)

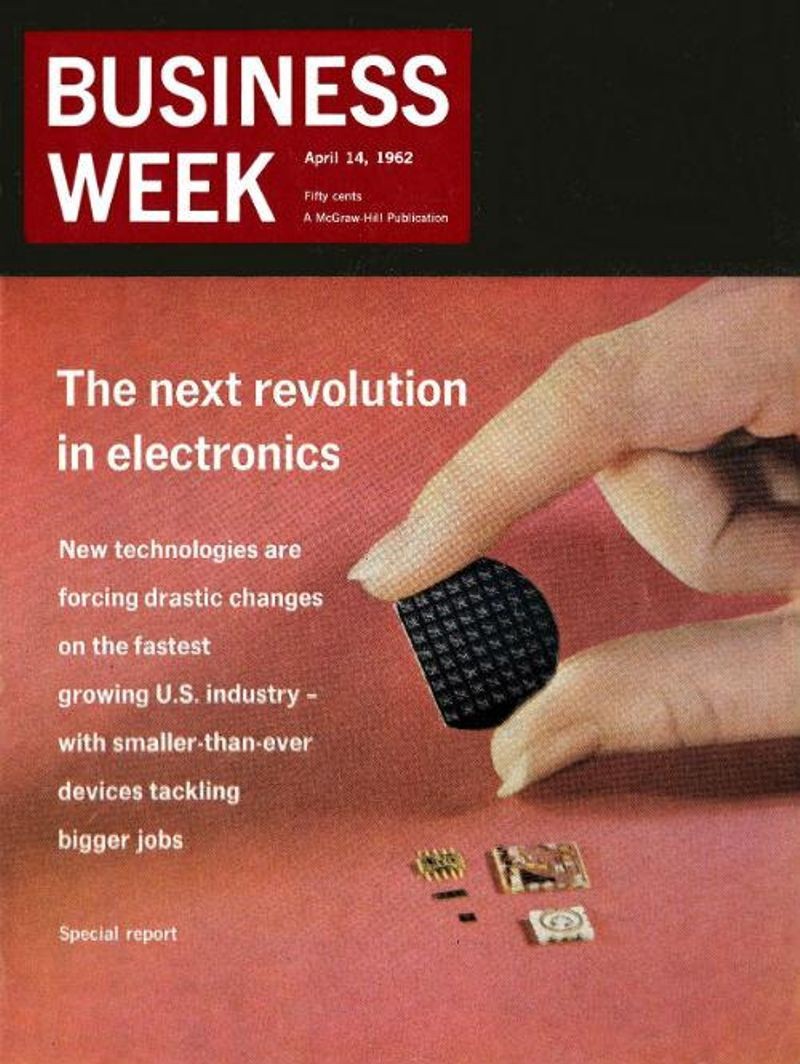

With sales growing rapidly at a high profit margin, in 1959 the parent company exercised its option to acquire all the shares of the new enterprise generating a financial windfall for the founders. By 1960 sales exceeded $20 million and the company was recognized as a leader in its field. The financial community began to take note after the company’s products were featured on the cover of Business Week magazine.

Business Week magazine featured Fairchild in a special report on “The next revolution in electronics.”

With this strong start (think of the company as the Google of the 1960s), Fairchild would probably have remained a successful player in the emerging semiconductor business. But a new manufacturing technique called the “planar process,” based on an idea described on pages 3 and 4 of his patent notebook by co-founder Jean Hoerni, sparked a revolution that changed the valley from just another emerging hub of the electronics industry, comparable to Boston or New Jersey, into a world-renowned center of innovation and entrepreneurial activity.

Planar made better and more reliable transistors, but most importantly it transformed the production of semiconductors from a handcrafting operation into a high-volume, electronic lithographic “printing” process that lowered costs and made them viable in new applications.

Co-founder Robert Noyce, realized that the technique also made it possible to interconnect multiple transistors into a complete electronic circuit on a single silicon chip. Noyce’s integrated circuit (IC), or microchip, enabled smaller, faster, cheaper, and more reliable electronic systems.

In 1965, another Fairchild founder, Gordon Moore, observed that continual improvements in the technology had allowed a steady increase with time in the number of components on each IC. From this data he projected an annual increase in complexity that emerged as a self-fulfilling prophecy, known as “Moore’s Law.” Engineers across the semiconductor industry accepted the challenge of squeezing ever more transistors onto their new IC designs. Continuing this trend, 50 years later manufacturers were routinely putting more than one billion transistors on a chip.2

The serendipitous combination of Hoerni’s planar process, Noyce’s conception of the IC, and Moore’s Law created a hotbed of innovation and entrepreneurship. In a 2016 interview at the Computer History Museum, Moore recalled, “It seemed like every time we had a new product idea we had several spin-offs. Most of the companies around here even today can trace their lineage back to Fairchild. It was really the place that got the engineer entrepreneur really moving.”3

The first Fairchild spin-off Rheem Semiconductor in 1959 was followed in quick succession by founder Jay Last’s Amelco Semiconductor, where he was joined by Jean Hoerni and Eugene Kleiner, and by Signetics, the first stand-alone IC company. While still at Fairchild, founder Kleiner had encouraged a lab technician to start his own company, Electroglas, to build specialized manufacturing equipment heralding the birth of a supporting ecosystem of specialty and service companies. In 1972, he co-founded the venture capital firm of Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. In the same year, fellow alumnus Don Valentine started Sequoia Capital Management. Both firms funded hundreds of technology-based startups.

Numerous other spin-offs, known as “Fairchildren,” followed as employees left to pursue dreams of creative and financial independence. Surveying the prior decade of growth in the region, in 1971 journalist Don Hoefler wrote an article titled “Silicon Valley USA” that described Fairchild’s influence on the industry. The name stuck.4

SEMI published several versions of a genealogy chart based on Hoefler’s research. A 1986 printing included 126 semiconductor companies that were traced directly to Fairchild.5

The first version of the SEMI Silicon Valley Genealogy chart published in 1977.

Founded by Moore and Noyce in 1968, Intel Corporation was the most influential and successful of the first generation of Fairchildren. A pioneer in memories and microprocessors, the company is today the world’s largest IC vendor with an enterprise value of nearly $200 billion and annual revenue of $55 billion. Intel built on the Fairchild management approach that emphasized meritocracy and openness over hierarchy that itself derived from the Hewlett-Packard approach of “management by walking around.” This encouraged direct employee interaction that evolved into today’s distinctive Silicon Valley management style of “flat” corporate structures and an emphasis on technical skills over other factors.

Other Fairchildren produced IC chips and technologies that enabled new communications, computing, and consumer products and, in turn, spun-off companies to exploit them. The best of them grew and thrived in the heady atmosphere of Silicon Valley where employee stock options played an important role in individual motivation, encouraging risk taking and creating, in some cases, substantial personal wealth. Some of the most successful semiconductor companies shown on the tree include AMD, Altera, LSI Logic, National Semiconductor, and SanDisk.

Many more companies failed than succeeded. Steve Jobs’s NeXT Computer and Gene Amdahl’s Trilogy Systems were two of the most spectacular fallen stars. But talented employees quickly found new opportunities in the fertile soil of the Valley’s entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Key product areas that grew into major industries included disk-drive storage, personal computers, local area networks, the internet, and mobile communication and computing devices. A host of new companies developing software applications running on these hardware platforms, including financial, education, desktop publishing and computer-aided design (CAD) packages, emerged in the 1980s. They were followed by internet and dot-com vendors in the ’90s (Sun Microsystems, Cisco, Netscape, etc.) and the mobile and social media barons (Google, Facebook, LinkedIn, etc.) of the new century.

Fairchild never fully recovered from the exodus of talent. Sales continued to grow through the 1970s but lagged in profits and significant new products. French oil services supplier Schlumberger purchased the company in 1979 but unable to reverse the decline sold the assets to National Semiconductor in 1987. National spun off several older commodity product lines to a group of managers at the former Fairchild plant in South Portland, Maine, in 1997 and the reconstituted Fairchild Semiconductor International Inc. was reborn there as an independent company. With a focus on power management devices, the new Fairchild prospered and was acquired in 2016 by ON Semiconductor Inc.

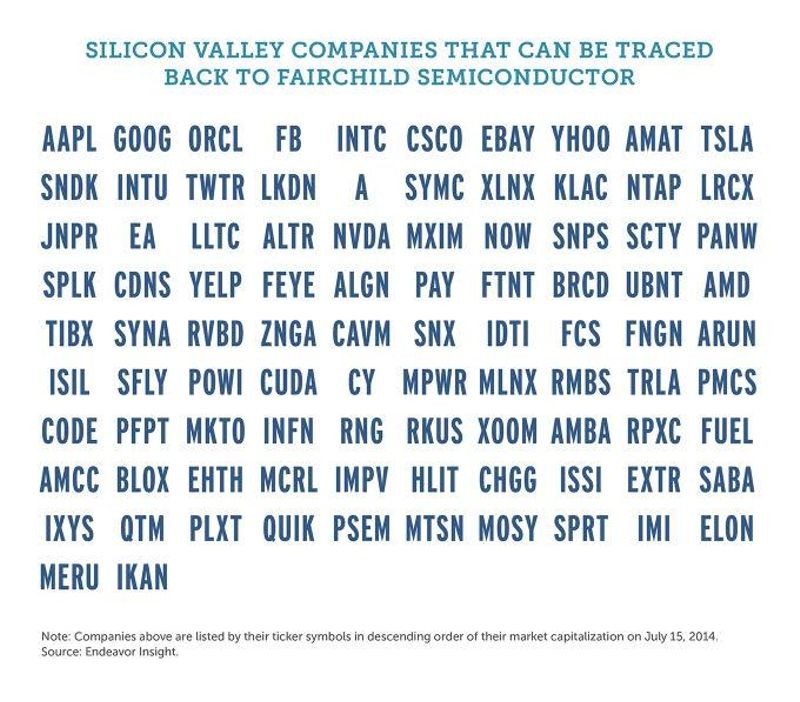

Public companies in 2014 traced back to Fairchild. Courtesy: Endeavor Insight

According to an Endeavor Insight report: in 2014 of the more than 130 Bay Area tech companies trading on the NASDAQ or the New York Stock Exchange, “70 percent of these firms can be traced directly back to the founders and employees of Fairchild. The 92 public companies that can be traced to Fairchild are now worth about $2.1 trillion, which is more than the annual GDP of Canada, India, or Spain.”

The planar technology derived from Hoerni’s two-page patent notebook entry 60 years ago has enabled the continuing delivery of more computing power at ever lower cost per function and changed every aspect of the way the developed world lives, works, and plays. It also catapulted Fairchild into the role of the “trillion dollar startup” that fostered multiple generations of high-value companies and the culture of entrepreneurial growth that today we celebrate as the Silicon Valley way.

On June 2, 2016, CHM’s Exponential Center celebrated its launch with a gathering of founders and builders of the Digital Age. Exponential honorees included Gordon Moore and Jay Last, the last two living co-founders of Fairchild, and Arthur Rock, who secured the financing for the young startup that changed the course of Silicon Valley.

Honorees at the Exponential Center launch gala: Gordon Moore (by video), John Doerr, Arthur Rock, Regis McKenna, Larry Sonsini, and Jay Last.