Happy Birthday Silicon Valley. Courtesy: Ms Silicon Valley

January 11, 2015 marks the 44th anniversary of the first known appearance in print of the name “Silicon Valley.” There are many opinions on how the former, bucolic orchard region at the southern end of San Francisco Bay, better known then as the “Valley of Heart’s Delight,” gained its distinctive new moniker. Observers from industry bloggers to the New York Times credit entrepreneur Ralph Vaerst, founder of Ion Equipment Corp. They claim he suggested the name to Electronic News reporter Don Hoefler, who then titled a column on local silicon computer-chip companies “Silicon Valley USA.” Published on January 11, 1971, the name stuck.

“Silicon Valley USA” Electronic News, January 11, 1971. Courtesy: Computer History Museum

Uncertainty over even the date of this first use arose from an error on page one of the paper. The masthead typesetter’s date carried over the year 1970 from the prior issue although the inside pages correctly show 1971. In 2010, docent Roy Mize at the Computer History Museum queried numerous historians, pundits, and colleagues on the origin of the name. Contemporaries recalled its use by government officials visiting local defense-oriented electronic companies in the late 1960s, but no one really knew when it first found its way into the lexicon. Jim Vincler, co-owner of Vincler Communications, Inc., Redwood City, CA recently described his recollection of how Hoefler came across the name:

“The name Silicon Valley was popularized by newspaperman Don Hoefler in 1971. Don was a columnist for Electronic News (EN), a weekly tabloid that covered the electronics industry. EN landed on the desks of electronics industry executives and managers on Monday mornings. These people did not start their work week before reading EN. They wanted to know what was being said about the people, the products, and the companies in the industry. EN was the Bible. If a story didn’t appear in EN, it didn’t happen.

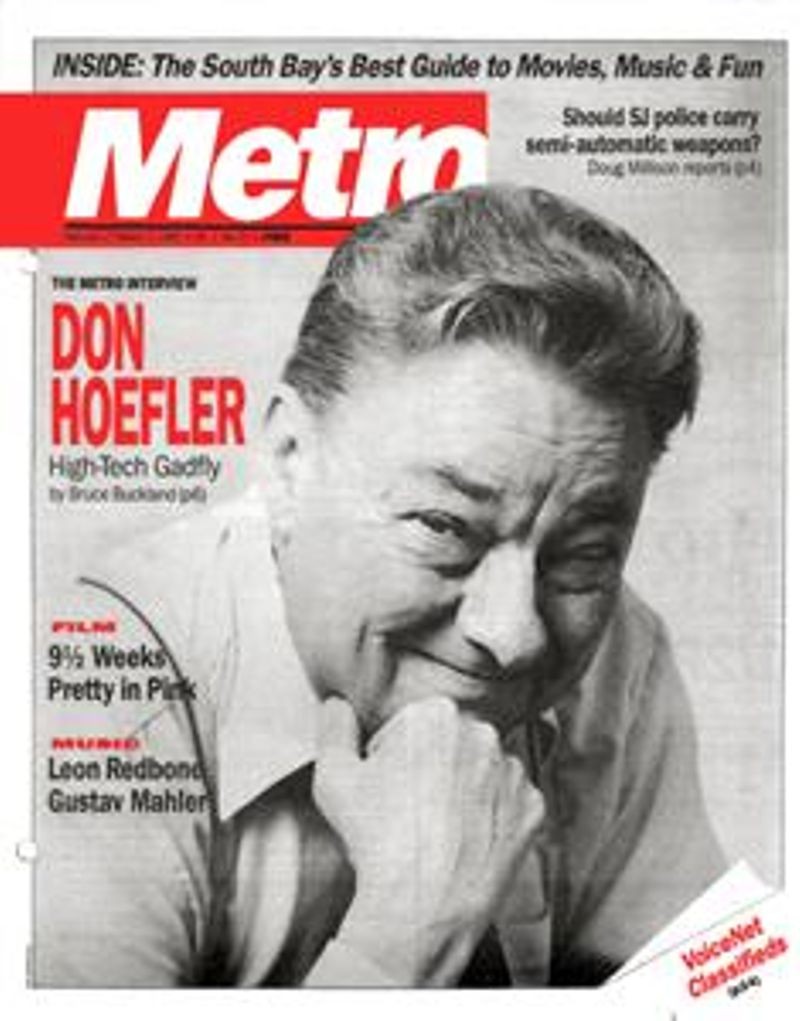

Don Hoefler, High-Tech Gadfly. Courtesy: Metro Magazine, 1986

Don was working for several weeks on a story about how the semiconductor industry blossomed in the Santa Clara Valley during the Sixties. One day a couple of marketing guys called Don and said they were going to be in San Francisco that day and invited him to lunch. I worked with Don as a reporter for EN and tagged along. During the lunch conversation, one guy said something about “Silicon Valley.” I saw Don’s eyes subtly light up like a poker player who had just filled a straight, as he asked, “Silicon Valley? Where’d that come from?”

The marketing manager said, “Oh, that’s what the guys call it.” We shared our amusement about the moniker that the industry sales people had created and then went on to other topics.

On our walk back to the office, I said to Don, “Cool name, huh?” He smiled.

When we got back to the office, Don, who was wrapping up his story, changed the title and wired it to EN headquarters in New York. The next Monday his story appeared with the bold headline: SILICON VALLEY, U.S.A.

And that’s how the world became aware of Silicon Valley.”

I asked Jim if one of the marketing guys was Ralph Vaerst. He did not recall the person’s name but said that it was definitely not Vaerst.

Jim Vincler, Electronic News reporter. Shared office with Don Hoefler in 1971. Courtesy: Jim Vincler

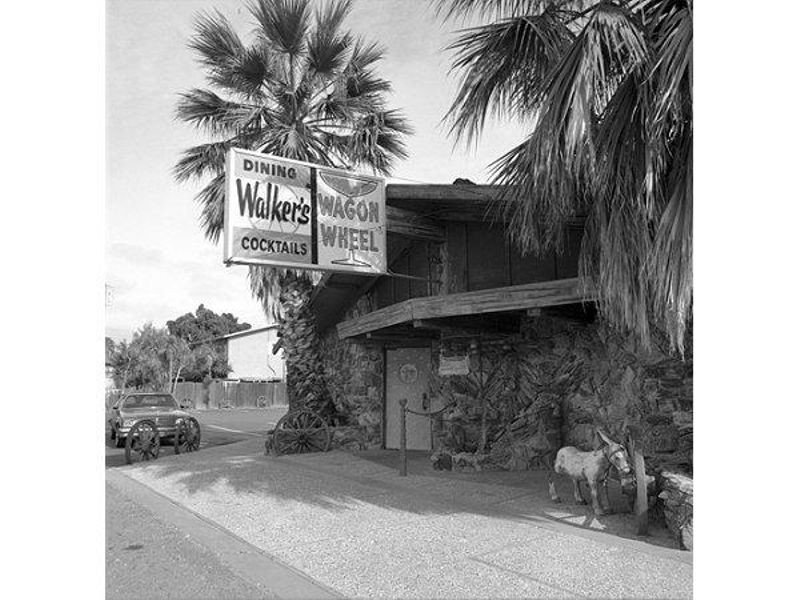

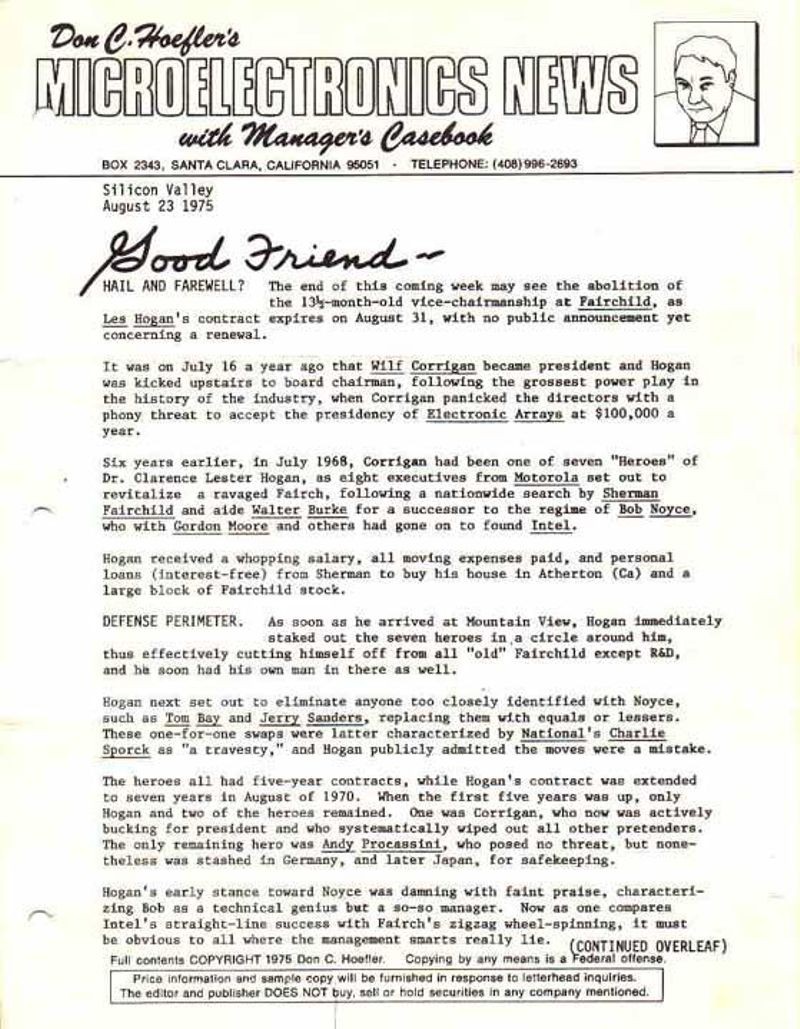

Don Hoefler left EN to start an industry newsletter called Microelectronic News (MN) that he continued to publish until his death in 1986. Loved by the rank and file but feared by management, he laced MN’s pages with tales of the follies and foibles of Valley CEOs. An obituary noted that “He was liked by some, disliked by many and read by all.” Corporate gossip, rumors of product failures, and insider details of financial shenanigans were gathered at his field office — a bar stool at Walker’s Wagon Wheel tavern. Copies were banned from many company offices. At one point the president of Signetics, Jim Riley, forbade his marketing people from entering the popular industry watering hole.

The Wagon Wheel, Mountain View, CA. ca 1969. Courtesy: Carolyn Caddes

Easily recognizable by the Conestoga wagon perched precariously on the roof at 282 E Middlefield Rd, Mountain View, CA, “The Wheel,” as it was known by regulars, lay at the heart of early Silicon Valley culture. Employees of fabled start-ups from Fairchild Semiconductor to Intel to Netscape retired to its dimly lit saloon to celebrate successes, mourn layoffs, recruit staff, and exchange solutions to common problems. Historians credit the sharing, cooperative style of the era with the rapid rise of the region as a leader in silicon chip technology.

Interior of the Wagon Wheel. Courtesy: Technology Communication, Inc. 1969

Razed in 2003 following entanglements over illegal gambling, the site remains vacant today. Several artifacts, including an original wagon wheel and a five-and-a-half foot section of its wooden bar, are on display in the Computer History Museum Revolution exhibit.

Industry veterans have donated copies of MN for the years 1972 to 1986 to the Computer History Museum. Bob Schreiner, founding CEO of Synertek, gave his personal collection to the Smithsonian Institution where issues from 1975 to 1986 are posted online at The National Museum of American History’s Chip Collection website.

Typical revelations of management machinations from 1975 are:

Microelectronic News, August 23, 1975. Courtesy: National Museum of American History Chip Collection

In a 1981 San Jose Mercury News article, Hoefler wrote “The rationale was simple enough: These revolutionary semiconductors are made in a valley, from silicon – not silicone, please – the second most-abundant chemical element (after oxygen) on Earth. How was I to know that the term would quickly be adopted industry-wide, and finally become generic worldwide?”

Author Michael S. Malone credits Hoefler with more than just popularizing the Silicon Valley name. He suggests that his multi-decade pioneering news coverage of the community as a collection of characters, eccentrics, and dreamers made him “the one that put the whole idea in our minds.”