On May 17, the Computer History Museum received a very special artifact for its permanent collection. This object, a highly-specialized computer system, rescued Bank of America—indeed the entire American banking industry—from being buried under an avalanche of paper and marked the earliest large-scale use of computers in business. The machine was called ERMA: the Electronic Recording Machine, Accounting, and the system came from the Bank of America building in Concord, California, where it had proudly been on display for several decades.

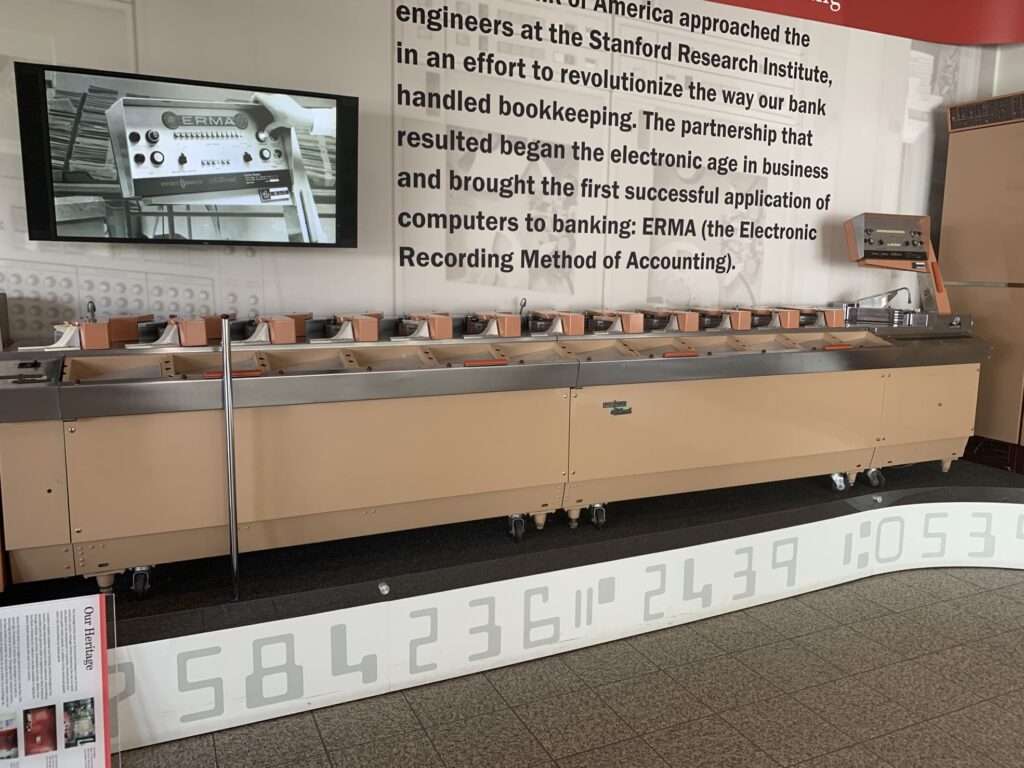

ERMA display at Bank of America’s Concord campus. Only the major parts of ERMA were preserved. Photo by Aurora Tucker.

Recently arrived ERMA units at CHM’s environmentally controlled storage facility. Photo by Aurora Tucker.

Before the mid-twentieth century, banking was a time-consuming, manual process. Deposits and withdrawals were recorded by hand, and account balances were calculated using mechanical adding machines. An experienced bookkeeper could post 245 bank accounts in an hour—about 2,000 in an eight-hour workday, or approximately 10,000 per week. (Even today, despite new payment systems like Venmo and Paypal, the average American writes 38 checks per year.) The system was prone to errors, and transactions could take days to process. And, because communication and record-keeping were largely done on paper, banks were limited in their ability to serve any but local customers.

Amy Weaver Fisher and James L. McKenney, "The Development of the ERMA Banking System: Lessons From History," IEEE Annals of the Historv of Computing, Vol 15, no. 1, (1993): 45.

After WW II, a booming middle class placed huge demands on American banks. At Bank of America (BofA), checking accounts were growing at a rate of 23,000 per month and branches had to close every day at 2 or 3:00 p.m. to handle the paperwork for that day. Even as early as 1948, the bank was processing over two billion checks per year.

ERMA was designed and built in mid-century. Note the atomic and “space-age” themes. https://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/access/text/2023/04/102726943-05-01-acc.pdf

Bank of America, called Bank of Italy until 1930, was founded in 1904 by A.P. Giannini as a small neighborhood bank in San Francisco's North Beach district. The bank‘s philosophy was to provide banking services to those not traditionally served by local banks, like immigrants and new small business owners. The bank’s success was phenomenal. By the end of 1941, Bank of America boasted 495 branches and $2.1 billion in assets. During World War II, California’s population and economy mushroomed, boosting Bank of America’s resources to more than $5 billion, more than any commercial bank in the world.

Preparing ERMA’s sorter for transport while A.P. Giannini looks on. Photo by Aurora Tucker.

Given this growth, and the expected growth in bank accounts after the War, BofA Vice President S. Clark Beise went to business machine companies like IBM and Burroughs to see if they could design a solution. But, these companies were not interested. Beise then approached the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) in Menlo Park, California, about applying automated methods to the problem, and they agreed to explore possible solutions. The proposed system was called ERMA and took some seven years of development to complete.

Led by SRI’s director of engineering, Thomas H. Morrin, ERMA's development was a complex undertaking that involved multiple teams and disciplines. On the BofA side, Al Zipf headed the equipment research department and coordinated development of important subsystems, including MICR. At its core, ERMA was a combination of hardware and software that automated banking operations. The hardware included a magnetic ink character recognition (MICR) system that could read information encoded on checks, a high-speed printer and sorter for check processing, and a computer to process transactions.

ERMA’s high-speed sorter. Built by GE in partnership with National and Pitney-Bowes. Photo by Aurora Tucker.

A major challenge was developing the software to process transactions. The team had to design a system that could handle millions of transactions per day, while ensuring that account balances were accurate and up-to-date. They accomplished this by using a combination of processing methods. Batch processing was used to process transactions in large groups, while real-time processing was used for high-priority transactions, such as those involving large sums of money. Interestingly, future AI pioneer Joseph Weizenbaum was on the ERMA software team, just a few years prior to writing his famous (and controversial) ELIZA chatbot program.

ERMA tape drives. Originally made by Potter Instruments. Photo by Aurora Tucker.

Though development was ongoing, the first ERMA prototype was ready by 1952, and by 1955, the design was established. SRI and BofA then looked for a vendor to build multiple ERMA systems (there would be 33 in total), and GE won the contract. Re-implemented using transistors by the newly formed General Electric Computer Department, ERMA was officially launched in 1959, after seven years of development. (The vacuum tube prototype was quietly donated to the engineering school of Arizona State University). Over the next two years, an additional 32 systems were installed, and by 1966, 12 regional ERMA centers served all but 21 of Bank of America’s 900 branches. Handling more than 750 million checks a year, the new ERMA was an immediate success. Within just a couple of years, it had shown the entire banking industry a new way of doing business.

ERMA was introduced to the world in September 1955 by future American president Ronald Reagan.

The SRI ERMA Development Team, c. 1950s. https://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/access/text/2023/04/102783425-05-01-acc.pdf

By 1961, ERMA was handling 2.3 million accounts. The system was eventually able to read ten checks a second, with errors on the order of 1 per 100,000 checks. ERMA contained more than a million feet of wiring, 5 input consoles with MICR readers, 2 magnetic memory drums, the check sorter, a high-speed printer, a power control panel, a maintenance board, 24 racks holding 1,500 electrical packages and 500 relay packages, and 12 magnetic tape drives for 2,400-foot tape reels.

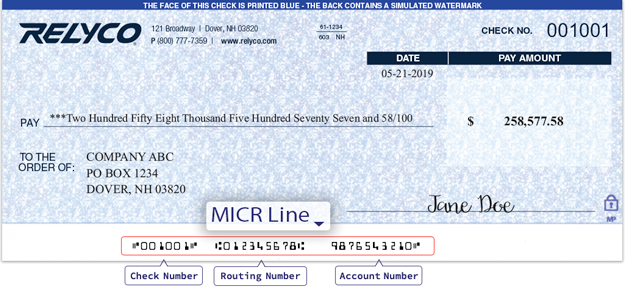

ERMA sped up processing by 80%, handling 33,000 accounts in the time it would take a human teller to process 250—and did it without error. The system relied on a clever encoding system: by writing the three important numbers required to process a check (bank routing number, the customer's account number, and the check number) using a special magnetic ink at the bottom of every check, ERMA could instantly get the relevant information for the transaction. Magnetic ink was chosen to provide resistance against smudging or wrinkling of the check, and the system—called Magnetic Ink Character Recognition—was quickly adopted by the American Banking Association as a standard. Soon all banks were using the MICR system invented for ERMA. Take a look at one of your checks today: the MICR characters are still there.

Modern check showing MICR characters at bottom.

In the 1970s, BofA offered a credit card linked to customer checking accounts, another first and so ERMA was also a precursor to modern electronic banking and credit card systems. More generally, ERMA demonstrated the potential of electronic data processing for banking transactions, got GE into the computer business, and was one of the earliest successful large-scale application of computers to business anywhere. Given that at the time the project started, electronic digital stored-program computers were less than five years old, ERMA was incredibly ambitious.

Today, electronic banking is a ubiquitous part of our lives—we can even use our smartphones to transfer money, pay bills, and check our account balances. When we take photos of our checks for mobile deposit, our smartphones read the MICR characters. ERMA’s legacy is still with us.

A Survey of Digital Computers, Ballistic Research Laboratory, 1961, GE 100 ERMA, p. 263 ff.

Interview with Dr. Robert Johnson, Manager, GE Computer Department, Annals of the History of Computing, vol 12, no. 2, 1990, pp.130-137.

SRI Alumni Hall of Fame: https://srialumni.org/halloffame-archive.html

Woodbury, David, O., Let ERMA Do it: The Full Story of Automation, New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1956.

Fisher, A. W., and McKenney, J. L., “The development of the ERMA banking systems: lessons from history,” Annals of the History of Computing, vol. 15, no. 1, 1993, pp. 44-57.

Head, R.V., “ERMA’s lost battalion,” Annals of the History of Computing, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 64-72.

1955 SRI newsletter, Research for Industry: http://ed-thelen.org/comp-hist/SRI_Newsletter_Oct55-1.pdf

GE Computer, GE 210 ERMA: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QfHMu75cfjg

Kim, H. Hannah, ERMA’s Whiz Kids: https://increment.com/teams/ermas-whiz-kids/