News and the flow of information are fundamental to how societies function, and there’s no doubt that technology has had a big impact on how people access, create, and share news—for better and worse. CHM held a public forum to examine the state of news today, explore where it may be headed, and share some inspiring models that are providing people with the news they want and need.

Here are some highlights from the three-part event.

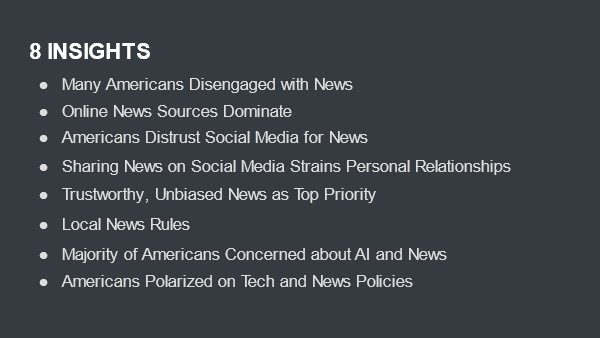

CHM’s Vice President of Innovation Marguerite Gong shared the results of a survey of a representative sample of 1,600 adults nationwide. A series of questions resulted in eight primary insights.

The survey results focused the event discussions in three primary areas: a broad view about technology, news, and a free press in a digital world; national news, local news, and the ways they inform each other; and, how innovators are creating, delivering, and sharing news in novel ways with the help of technology.

Richard Gingras, vice president of news at Google, took the audience back to 1791, when the First Amendment was established. At that time, people shared ideas through the printing press, and it took weeks or even months for debates to reach a national stage. Technological advances like the telegraph, radio, and television allowed voices to carry faster and farther, but publishing information was the privilege of the few.

That changed in the 1990s, when the internet revolutionized communication and enabled anyone to share their voice in the public square. It also changed how people are informed, how they form opinions, and how they perceive the world and each other.

Richard Gingras describes the fragmentation of news.

Along with technological advances like generative AI that can potentially serve the information needs of local communities as well as spread misinformation, Gingras notes that journalism must adapt to changing media forms and the different ways that people communicate and understand society, including through social media. The political sphere has adapted the internet's capabilities to speak to voters and build alliances more quickly and effectively than journalism, resulting in the rise of authoritarians and the demise of democracies.

We’re at a seminal point in the role of our digital societies and the role of the press in them, says Gingras. We should admit that what we’re actually concerned about is not the dangers of machines, but of ourselves.

Chris Shipley, author and curator of Newsgist, moderated a panel that featured Cheryl Phillips, the founder of Big Local News at Stanford University and David Walmsley, editor-in-chief of Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail. They discussed how to build trust with local communities and fill information gaps.

For Walmsley, community engagement in a large country like Canada, with a population dispersed over six time zones, poses challenges.

David Walmsley advocates building trust by listening.

Walmsley uses social media’s free platforms, including TikTok and Instagram, to improve accessibility to the newspaper’s trusted brand. Social media also allows the paper to offer news and information in a way that is more attractive or comfortable to people like young women.

Cheryl Phillips’ Big Local News collects and aggregates local data like school enrollment and police stops to create large datasets. The local data provides a good sense of what’s happening that needs to be addressed by a local government, and the larger dataset can be used to identify patterns that call for policy changes at the federal level.

Cheryl Phillips collaborates with the AP and local journalists.

So, asked moderator Chris Shipley, how do newspapers and journalists regain people’s trust today? Walmsley believes it’s important to share and explain your methodology—talk about how you chose the stories you did, for example, and why you declined others. Journalists must explain the effort that goes into the news. Phillips says its crucial to ask people exactly what information they want to see and give it to them—sometimes it might just be unvarnished facts on which they can take action rather than beautiful, comprehensive graphics of all the data that's been collected.

Dawn Garcia, director of the John S. Knight (JSK) Journalism Fellowships at Stanford University, moderated a panel featuring alumni of the program who spoke about the innovative models and the technology they use to help keep diverse communities engaged and informed.

Venture philanthropist Tracie Powell is the founder and CEO of The Pivot Fund. She invests in community-based, grassroots newsrooms, particularly those led by and for people of color, helping them scale their work to reach more audiences and generate revenue to become more sustainable.

Tracie Powell invests in local news.

Maritza Félix founded Conecta Arizona during the pandemic to debunk misinformation. What started as a group on WhatsApp grew rapidly into a radio show, then a newsletter, and now a podcast that reaches more than 100,000 people. She hosts Cafecito (coffee) every day on WhatsApp to discuss the news of the day, bringing in experts once a week to answer questions directly.

Maritza Félix shares news on WhatsApp.

Candice Fortman is the executive director of Outlier Media, a non-profit newsroom in Detroit that provides information 24/7 through an SMS text-based platform as well as undertaking investigative and accountability reporting. To find out what Detroiters want to know, Outlier Media conducts an annual assessment, asking questions over text message, like, “If you had a reporter working with you for the next 24 hours, what would you have them figure out for you?” They also mine public record information requests, and Fortman notes that complaint data is a very good indicator of where there are accountability and transparency gaps. Outlier Media also fosters community journalism in partnership with an organization called Documenters.

Candice Fortman empowers citizen journalists.

Fortman closed with a plea to the techies in the audience at CHM: SMS technology is always breaking—please fix it! The same might be said of the news—it may be broken, but there are plenty of thoughtful and creative people working to fix it. Let’s join them.

Tech X The Future of News | CHM Live, June 20, 2023

Blogs like these would not be possible without the generous support of people like you who care deeply about decoding technology. Please consider making a donation.