As a student, Metcalfe (left) connected computers to the early ARPAnet. He teamed up with Stanford graduate student and radio expert David Boggs (right) to implement Ethernet, and later to collaborate on internetworking.

40 years ago on May 23rd, 1973, a young researcher named Bob Metcalfe outlined his new “Ethernet” concept in a memo to his managers at Xerox PARC. Radio and hardware wizard Dave Boggs turned it into a working reality, the network that would connect Alto computers to each other, and to laser printers, and remote servers. Today, Ethernet is an almost unnoticed part of the fabric of modern life; we use it for virtually all of our local networks, from office, to datacenter, to home and cafe. Its wireless offshoot, Wi-Fi, keeps us linked through the air.

Today, May 22nd 2013, the Ethernet Innovation Summit brings together Bob Metcalfe, Dave Boggs, and many other Ethernet and networking greats to the Computer History Museum for a birthday celebration, a look back, and a reflection on its future.

But despite its familiarity, few realize how Ethernet got from Bogg’s windowless lab to your home router, or the twists and vagaries of the long battles in which it fought off rivals from ARCNET to Token Ring. Fewer still know how wired Ethernet was directly modeled on a wireless standard, ALOHANET, but later spawned its own wireless variants; or the story of how Bob Metcalfe and his 3Com colleagues brilliantly maneuvered a proprietary system into an international standard.

Early versions of Ethernet used well-established, television-type coaxial cable technology. But the difficult-to-use shared coax later gave way to telephone-style wiring.

Today we’re releasing five historic 1980s interviews that tell parts of the local networking story. They are with Bob Metcalfe, David Liddle, Gordon Bell, Bruce Hunt, and John Davidson, and are being released for the first time. They come from a very unique source, the James Pelkey Collection, and you can find the first batch here, with more to follow.

The first person to go out and systematically research the story of Ethernet – and of the Internet, and modems, and all the networking devices and standards and rivalries that underpin the online world – was an aggressive young venture capitalist named Jim Pelkey. As he traveled the globe in the late 1980s doing deals in the datacom and networking sectors, he took side trips to record interviews on a high-quality tape recorder with an expanding list of major networking pioneers.

Jim Pelkey, networking historian and venture capitalist

This historical hobby was only partly related to Jim’s daily world of high-powered meetings and fierce negotiations. But he got more and more absorbed by the project, and his goal evolved into writing the first comprehensive history of computer communication and networking. He would tell the story of the industry not just from a technical perspective, but also try to get at the central question of how innovation happens: what’s the recipe? Which are the ingredients, from talent, to standards, to investment, to luck?

Paul Baran, inventor of packet-switching, was his main mentor in the effort, joined by ARPAnet architect Larry Roberts and conference organizer and emcee extraordinaire Dan Lynch.

Less than a year into the project, Jim was gravely injured and lost the use of his legs.

To the extent I had thought about it at all, I always assumed being paraplegic meant simply not feeling anything in your lower body. But when I got to know Jim a few years ago, I realized the reality can be far worse. Many paraplegics like him battle near-constant, severe pain, and medication can leave them tired and dopey.

As he slowly rebuilt his life over the months and years that followed his injury, Jim began to assemble his book from over 80 interviews and thousands of documents. As the Web emerged he was intrigued by the possibilities of hypertext, and he turned it into not just a book but a site that can be read and recombined in numerous different ways, depending on the readers needs. But his energy was severely limited.

Still, he went on to become Chairman of the Board at the Santa Fe Institute and to invest part time as a VC. He also turned to meditation and spiritual practices to cope with both his physical discomfort and the grim limits of his situation. Both he and those who knew him felt that he changed in this period, from a ruthless, type-A businessman to a gentler and more reflective seeker. In the words of Paul Baran: “I knew Jim before the injury. But I became friends with him after.”

A few years ago he approached the Museum. Trustee Gardner Hendrie and I negotiated an understanding around both his audio oral histories and his online book, History of Computer Communications. Along with his interviews the book is now a resource of the Internet History Program at the Museum, and you can also access it from the sidebar of the “Explore” tab on the Museum site. We realized quickly that Jim had lost none of the finely honed negotiation skills he’d developed as a young businessman.

But when Jim did his interviews in the late 1980s and early ‘90s, he didn’t ask the pioneers to sign releases; after all, they were just research interviews for a book. For CHM to release the interviews publicly, we needed permission from the subjects. Over the last year and a half Oral History Coordinator Jenny De La Cruz, Jim, and myself have worked to track down these long-ago subjects and get their permission. Jim and Jenny have also written abstracts for the interviews, and Jenny has found and coordinated volunteers to edit many of them.

Today, we’re releasing five of them for the first time ever; Bob Metcalfe, Gordon Bell, John Davidson, David Liddle, and Bruce Hunt, with more to follow. These join and complement the over 600 video interviews in our own Oral History Collection.

One glaring omission is Dave Boggs, co-creator of Ethernet. He has agreed to an oral history interview by CHM, and we hope to schedule that soon.

Jim reached a decades-long goal this month. With help from networking standards historian Andrew Russell, he finally finished the 25,000 word concluding chapter of his book, which summarizes the internetworking battles of the 1980s. Their outcome was not obvious. As he points out in his concluding note: “I thought, and I believe many if not most people thought, that the OSI communication protocols would be the future. Of course, they are not, nor are any other proprietary protocols, such as SNA or DECnet. TCP/IP [the suite of Internet protocols] is now nearly on every computer.”

Jim hopes to have that finished chapter incorporated into his Website over the next few months, and we’ll announce it here when it is ready. He’s looking for volunteers handy with DreamWeaver to help whip it into final form; you can write him at jim@jimpelkey.net.

Today, Jim Pelkey lives on Maui, in a beautiful home high on the slopes of Haleakala, the 10,000 foot volcano that crowns the lush island. My wife and I visited him a couple of years ago so I could go through his many filing cabinets full of papers, and negotiate the relationship with the Museum. In his mid-60s, Jim seemed vigorous; he worked out for hours a day in his home gym with a view of the sea far below. He had remodeled his expansive bathroom into a wheelchair user’s ideal, so beautifully that it was featured as a photo spread in a magazine on accessibility. When I went with him to an art opening his mix of charm and commanding presence immediately gathered an entourage, many of them women. But his good hours were few; he rose late and retired early, and his pain was ever present. For 25 years Jim has battled obstacles few of us will ever even imagine, and now completed a truly heroic task.

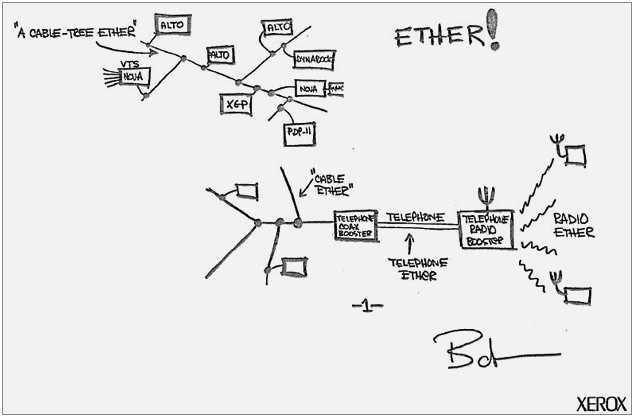

An original Ethernet circuit diagram.

While most networking histories stick to a single well-worn track, the creation of the ARPAnet and then the Internet in the United States, Jim’s interviews and book cover both the competitors to those efforts, and the local area networks – like Ethernet – that developed alongside them. He also addresses the larger world of data communications, interviewing modem makers, and the CEO’s of companies that make digital PBXs and other backend equipment. His interests are not just about the technologies, but the business decisions behind them. His work is my go-to source for the making of the infrastructure of our online world, and I am deeply pleased that it is complete.

Jim’s interviews have been invaluable to my own research; I’ve often read them to prepare for my own video oral histories with the same subjects, from Louis Pouzin to Len Kleinrock, over two decades later. I’ve discovered that the good news is most people don’t contradict themselves, nor forget nearly as much as they fear.

Congratulations, Jim.

Happy Birthday, Ethernet!!!