CHM IBM 1401 Restoration Team, June 2013

Is anyone willing to lead a project to restore an IBM 1401?” Mike Cheponis enthusiastically asked with a glint in his eye. I knew Mike after attending several of his DEC PDP-1 restoration sessions at the Computer History Museum. While most of my late night college hours were spent on DEC, UNIVAC, and SDS computers, I had little exposure to IBM in the day. After designing central processors and leading-edge workstations at Xerox (1979) and Sun (1984), with a new position at IBM Research and a curiosity about the history of early computers, I naively accepted the challenge. A few moments later, I asked: “What exactly is an IBM 1401?

I was also intrigued about whether it would even be practical to restore a transistorized computer from the early 1960s, especially after thirty years of uncontrolled storage in a questionable climate. After posting “An IBM 1401 Needs Help” ad in the IBM San Jose Retirement Newsletter, I was grateful when about a dozen retired IBMers stepped forward to bring the 1401 back to life. As they were mostly customer and manufacturing engineers who had serviced IBM 1401s in its day, I couldn’t have wished for a better team of experienced, enthusiastic, and witty story telling volunteers. After securing donations, IBM and Maersk crated and shipped a 1401 from Germany plus its crucial documentation to the CHM in the spring of 2004.

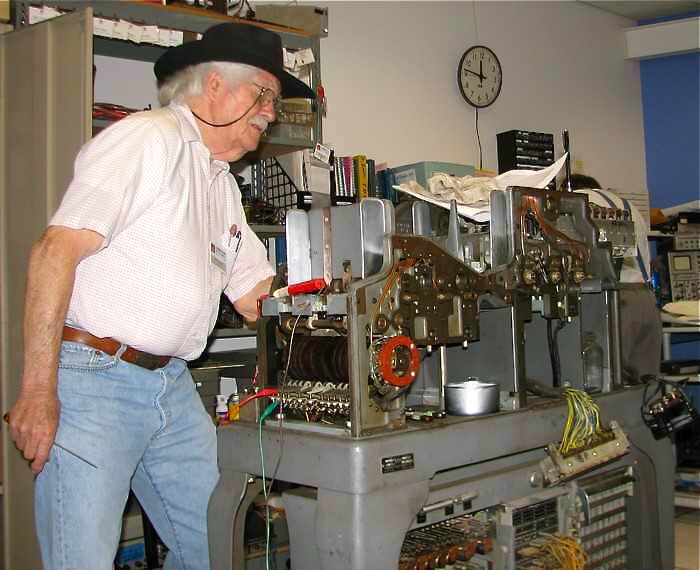

Bob Erickson restored a 513 Reproducing Card Punch, shown here, and an 077 Collator from the 1940s. Both used control panel “plug boards” to define how they processed stacks of punched cards. Decades of wiring control panels was replaced with software applications running on stored program computers, primarily the IBM 1401.

When the German 1401 arrived, the full extent of the challenge hit us: a central processing unit with 3,000 printed circuit cards, mechanically driven card reader/punch, hydraulically controlled chain line printer, and six reel-to-reel vacuum-column tape drives. The acquisition also came with some even older punched card equipment: 077 Collator, 082 Sorter, 513 Reproducing Punch, and 026 Keypunches, all about which I knew nothing! The project was daunting: not only would it involve restoring the main frame of electronics, comparable to the PDP-1′s, but restoring the other equipment would be like fixing about a dozen old automobiles! It would also consume about 12,000 watts of 50-Hz power. I needed project leads for each of the different subsystems and a large enough team that would stick it out for an unknown number of years going forward.

Sam Sjogren uses the team’s custom-designed 729 tape emulator, which can simulate up to 6 tape drives, including its front panel buttons. It sends and receives bona fide analog signals to/from the tape control unit in the 1401.

As the team began work on the German 1401, the extent of the corrosion became worrisome, especially on exposed surfaces, mechanical moving parts, and transistors. Transistors!? Low and behold, the metal cases and leads of the early alloy-junction germanium transistors and crystal diodes contained iron! Many had rusted, resulting in bizarre failure modes when their hermetic seals, as a matter of course, were compromised.

Ron Williams (1401 CPU lead), Allen Palmer (729 tape unit lead), Bob Feretich, and Grant Saviers search for a bug in the Connecticut tape control circuits.

By meticulously debugging 1401 diagnostic instruction sequences, step-by-step, several faulty SMS circuit cards were found and repaired each passing month. In all, 130 failed SMS cards were located and fixed. Working in parallel, the 729 tape restoration group elected to entirely re-fabricate the drive mechanicals and to build a custom tape drive analog/PC-controlled hardware emulator to debug the 1401’s tape controller unit. The 1403 printer didn’t require as much work, but relays and corroded card handling paths in the 1402 card reader/punch required constant attention.

On a rainy day in Darien, Connecticut, riggers lift our “new” IBM 1401 Central Processing Unit out of the basement where it performed data processing tasks for the home’s family run business from 1972 until 1995!

In 2007, as I fretted that we may have procured an impracticable number of rusted out transistors, I got a surprise call offering another 1401! This similar system had been operated by a mom-and-pop business up until 1995 in the de-humidified basement of their family home in Darien, Connecticut. Local riggers extracted it from the basement and when IBM and McCollisters shipped it to the Museum, the German 1401 seemed to recognize a sibling rival, and offering up its last faulty transistor, started to behave correctly! As I expected, only about thirty faulty SMS cards were found in the Connecticut 1401 and it was up and operational within six months. Even though a single 1401 system comprises over half a million discrete components (!), our two 1401s do operate reliably for many months before a failure. Back in its era, it’s reported that 1401s ran for over six months before needing service.

Kids of all ages enjoy the exhilaration of using an 026 Printing Card Punch. Frank King (1403 printer lead), shares tales about what IT life was like in the era.

The biggest joy for the volunteer team, who have put in over 20,000 hours, is not repairing the old equipment, but demonstrating the “compusaurs” to families and younger visitors. Kids’ and adults’ eyes light up as they punch cards on a keypunch, witness a clattering chain printer, stand before the human-sized spinning tape drives, gawk at its big size, and be taken aback by its “low cost” ($3 million in today’s dollars). Visitors experiencing our running 1401s feel as if they’ve stepped into a technological time machine!