Charles Bourne recalls pioneering experiment with Doug Engelbart at SRI in 1963. Watch the full oral history.

Charlie Bourne was an expert in computerized search for 40 years before Google. CHM has recently finished cataloging his unique collection of materials documenting the history of online search and information systems from the 1950s onward, supported by a generous grant from the National Archives.

Many of us assume that retrieving and browsing information online arose with the web in the 1990s, instantly catapulting us from thumbing through dusty card catalogs to the millisecond response time of modern search engines. Older computer insiders may have vaguely heard of one or two specialized earlier computerized services, like LexisNexis for journalists and lawyers, or the pricey Dialog.

LexisNexis

The real history is longer and richer. Full-text online search was prototyped in the early 1960s—partly through Charlie's work – and commercialized by decade's end. But pre-computer machine-aided search goes all the way back to punched card sorters. These were conceived in the 1830s and built in the 1890s, during a period of huge advances in card catalogs and other manual retrieval techniques. Real-time, interactive search was pioneered in the 1920s with Emmanuel Goldberg's microfilm "search engine," built into a desk.

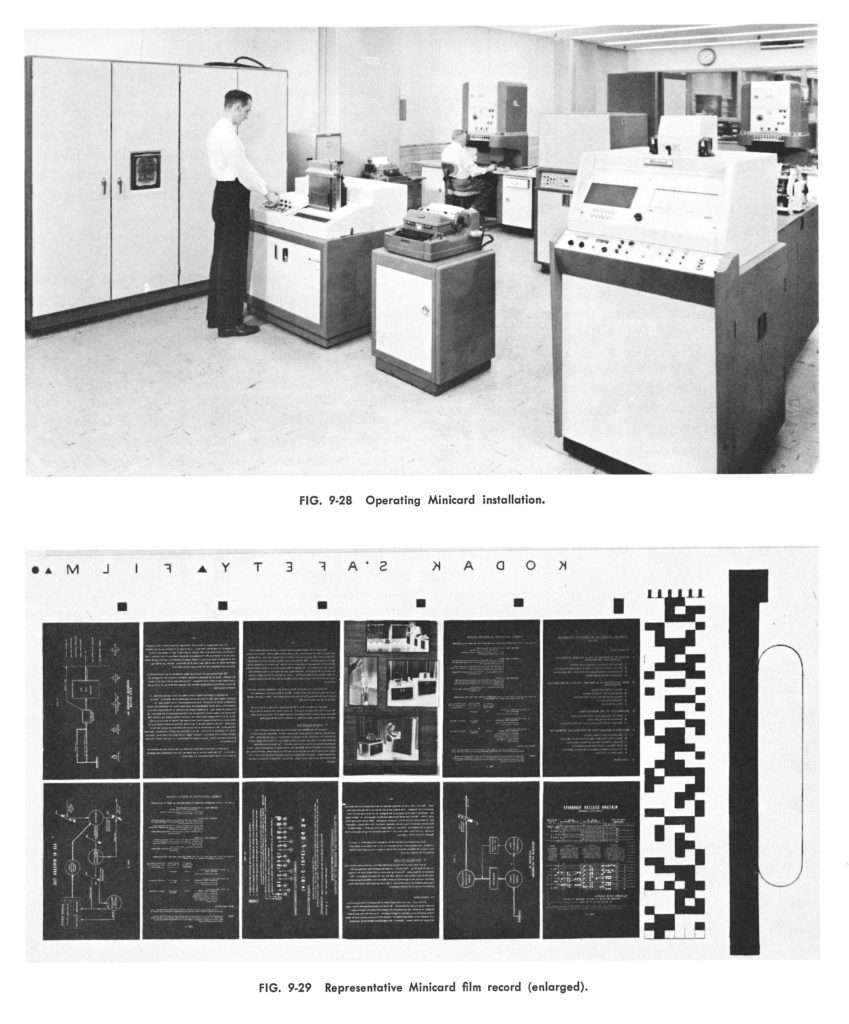

By the late 1950s, manufacturers were selling a Rube Goldbergian mix of different storage and retrieval technologies to governments, corporations and the military: Rapid Selectors capable of searching 330 pages per second on microfilm, magnetic media or microfilm integrated into punched cards, and various futuristic looking viewers. Some were already computer controlled, and major conferences were starting up around how computers would soon revolutionize the entire field.

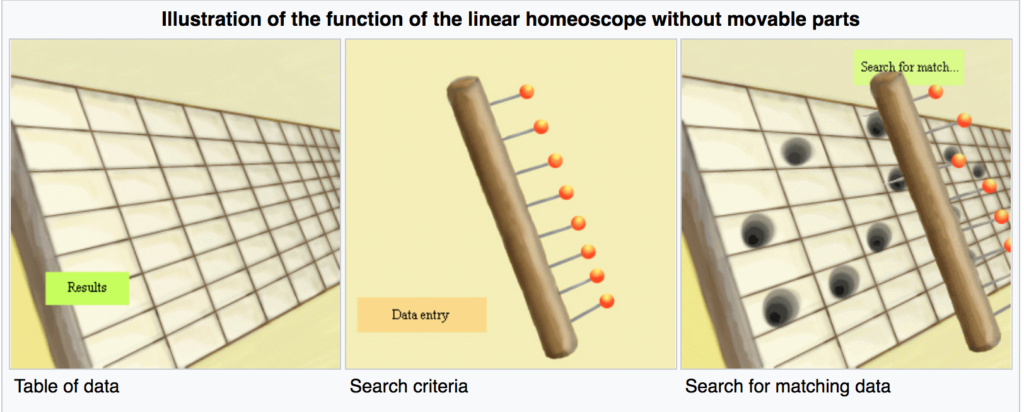

Semen Korsakov, modern illustration of the function of his 1830s punched card concepts for researching ideas (Ideascope) and more. Source: Wikipedia

This is the background against which Charlie Bourne, a student of computing great Harry Huskey, was turned on to information retrieval by another one of his professors at UC Berkeley, Douglas Engelbart. As we'll see he has spent the rest of his long career at the intersection of the two fields.

One reason the early history of online information remains unfamiliar to computing folks is that much of it took place under the auspices of library science research, and professional organizations like Association for Information Science and Technology (ASIS). Even in recent decades, the computing and information retrieval professions operate largely in parallel tracks, broken by occasional moments of cross-fertilization—like the NSF-funded Digital Library Project that led to Google.1

Charlie Bourne's collection, which contains materials both from his own varied work and from the research for his books, offers a truly unique chronicle of the two fields' shared history. Processing of the collection was supported by an Access to Historical Records grant from the National Archives’ National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC). The NHPRC supports projects that promote access to America’s historical records to encourage understanding of our democracy, history, and culture.

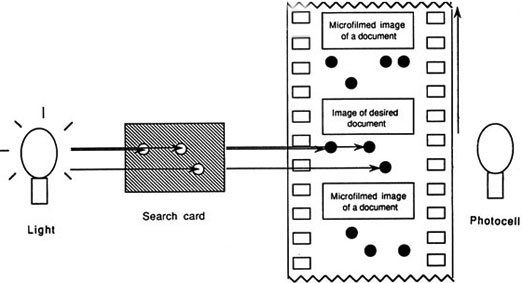

Operating principle of Goldberg's microfilm retrieval machine, from patent drawing.

After graduating Charlie took a job at Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International), where he evaluated and wrote specifications for a number of retrieval systems: a microfilm system to handle three million records for the Air Force, an automated system to coordinate collecting and translating Soviet bloc literature, a Navy database to inventory every kind of radio signal from enemy equipment for shipboard use, and so on.

His old professor Doug Engelbart soon moved to SRI himself, and in 1963 Charlie helped him with a pioneering experiment he described in his 2015 oral history for CHM, excerpted at the top of this blog.

Charlie wrote the specification for perhaps the earliest example of modern online search, where you search the full text of documents on a remote computer. Lynn Chaitin did the programming. The remote computer was one of the behemoths custom-built for the SAGE nuclear warning system. Engelbart had arranged to use it through his funder, computing giant J.C.R. Licklider at ARPA.

The test worked perfectly, even allowing Boolean qualifiers like "and" and "or." Licklider himself was researching what would become his 1965 book Libraries of the Future, which predicted that by the year 2000 all literature would be online, and searchable, with the massive task of cataloguing eased by weak AI.

In 1963 computerized search itself was not new. All of the search features they tested from SRI—and many others—had been demonstrated before on batch-processed systems using punched cards. These included natural language queries, relevance scoring, stem and "wild card" searching, proximity and phonetic searches, alternate and weighted search terms, and automatic searching on synonyms. What was new was searching in real time, in a live back and forth session with a computer rather than loading up a deck of cards and waiting for a result.

Charlie himself had been busy, earning his master’s degree from Stanford in 1963 as a young father and completing his first book. Methods of Information Handling won the American Documentation Institute (ADI) Book-of-the-Year award. He left SRI in 1966 to serve as a vice-president at Information General Corporation while consulting widely in the information industry, as he did for most of his long career.

One early client was the CIA, for whom he evaluated a gigantic computerized system for automatically translating intercepted Russian documents into English (it wasn't quite ready). Others would include the Stanford University Libraries, UNESCO, the National Academy of Science, the Library of Congress, the National Agricultural Library, US Patent Office, and United Nations, and Central Intelligence Agency. Some of the early systems Charlie evaluated were fully computerized, but those handling images usually included an analog component such as microfilm. Computer memory was too expensive to make high quality graphics practical until the 1980s. Charlie was also active in professional organizations, serving as president of ASIS where he helped demonstrate Doug Engelbart's work to both computing and information science colleagues.

Analog information retrieval equipment, from Bourne's 1963 Methods of Information Handling.

In 1971 he became a professor at the School of Librarianship and Information Studies at UCB (now the School of Information), while also directing the University's innovative Institute of Library Research. He oversaw seminal work in taking UC libraries card catalogs online. His 1980s book Technology in Support of Library Science and Information Service drew on those experiences.

In 1977 he moved to pioneering online information provider Dialog Information Services, working his way up to Vice President of the General Information Division. Dialog was a key early example of the crossover between information science and the computing industry. Founder Roger Summit had been part of Lockheed Missiles and Space Corporation's mid-1960s Information Sciences Laboratory (1964). He had built his ideas about iterative search—a "dialog" between the user and the computer—into a separate online search division for Lockheed. (This was very different from the "take your best shot" approach of modern search engines, where you generally need to run a new search to refine irrelevant results). Dialog licensed access to leading databases in a variety of fields, which you could search with its powerful tools. While the overall amount of information was far smaller than on the modern web, it was far, far more relevant and better organized.

But Dialog was—often more than the equivalent of $50 per hour. Even as computer equipment plummeted in price between the mid '60s and the early '90s, the subscriptions to a growing variety of databases remained a major cost. Dialog and competitors like LexisNexis were for corporate budgets. Only in the web era would this kind of deep, general search trickle down to the rest of us, both with keyword search engines like InfoSeek, AltaVista, and Google, and with more traditional hierarchical directories like the early Yahoo! or the later Wikipedia.

Charlie retired from Dialog in 1992 and continued his consulting work while preparing a third book. A History of Online Information Services, 1963-1976, which he coauthored with Trudi Bellardo-Hahn, came out in 2003. It won the Association for Information Science and Technology (ASIS&T) Book-of-the-Year award. Charlie lives in Menlo Park.

The detailed Finding Aid to the Charles Bourne Collection is here. The contents of the collection range in date from 1947 to 2016, consisting of materials related to Bourne's pioneering career in the database and information retrieval industry, including his work at Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International), UC Berkeley, and Dialog Information Services. The collection contains Bourne's personal project files, which include papers, presentations, and other activities related to his professional work, including his book A History of Online Information Services, as well as the unpublished work Cost Analysis of Library Operations. The collection also holds Bourne's subject files on a range of topics, including organizations developing search systems, people working in the field, and database suppliers. These subject files contain technical reports, instruction manuals, internal reports, clippings, articles, correspondence, meeting notes, and some images and recordings. Additionally, there is a large collection of serials, conference proceedings, and books relevant to Bourne's computer and information science interests. The materials from a number of late 1950s and 1960s conferences on computerized search and browsing

In addition to papers, the collection includes examples of several kinds of pre-computer information retrieval media, such as punched cards with embedded microfilm.

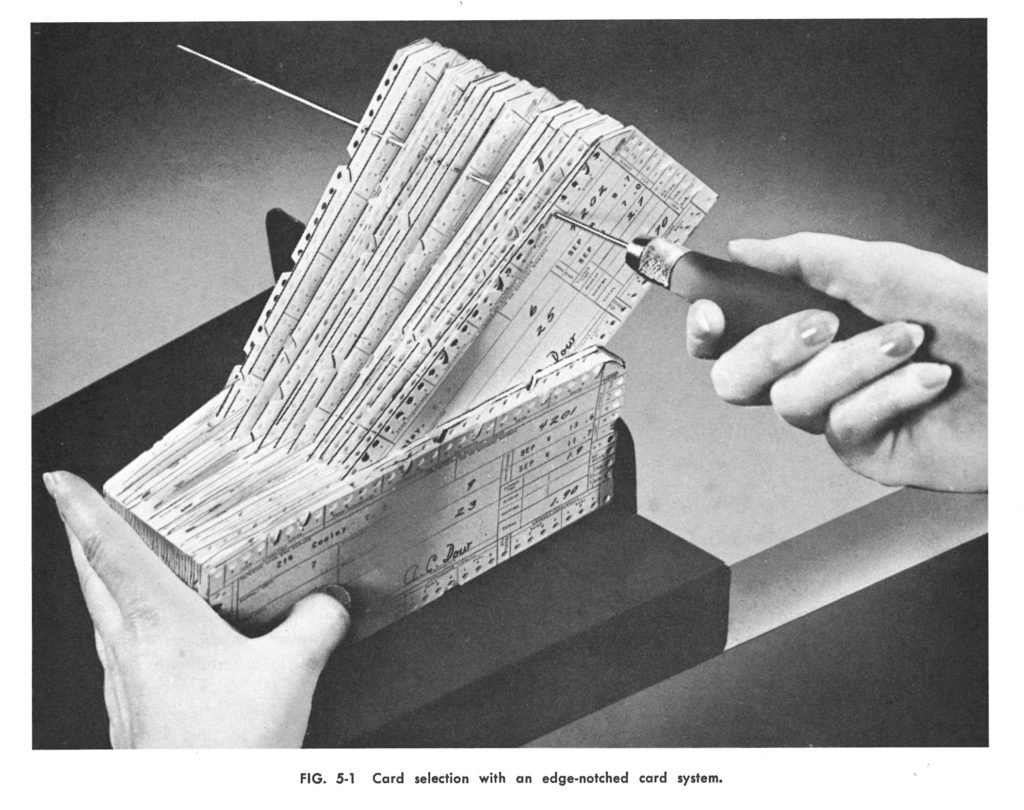

The Bourne Collection includes examples of pre-computer information retrieval media. This illustration of edge-notched cards is from Bourne's 1963 Methods of Information Handling.

Michael Buckland of the UC Berkeley School of Information is a leading information scientist who introduced Charlie Bourne to me, and suggested to Charlie that he offer his collection to CHM. Dr. Buckland served as an advisor on pre-computer "world brains" for the web gallery of our permanent exhibition Revolution, and is internationally known for his groundbreaking research into Emmanuel Goldberg of Zeiss-Ikon. Goldberg's actually-built 1920s microfilm "search engine" presaged the remarkably similar Memex concept of Vannevar Bush by over a decade.

By Michael Buckland

When I first met Charles Bourne 50 years ago in 1969 he was already a leading figure in the world of documentation and information science. He was actively engaged as convention chairman for the forthcoming annual meeting of the American Society for Information Science (ASIS) in San Francisco that fall. Reflecting his personal outlook, the convention was planned with two special emphases: An effort to include participants from other professional groups with interests related to ASIS and the incorporation of attention to new techniques for information dissemination and exchange. The latter including attention to online systems and ways to match attendees with sessions relating to their interests. He was also, already at that time, President-elect of ASIS, a status which is a unique mark of respect by one’s peers. Later I had the benefit of being one of his colleagues when he was a professor at the University of California, Berkeley’s School of Library and Information Studies, where he directed an innovative, multidisciplinary multi-campus research organization, the Library Research Unit, which engaged in a wide range of useful studies of information storage and retrieval systems.

Charlie achieved his reputation not only by his ability but also by being well-organized. He made it his business to find out who else was interested in document management, data management, and library automation, especially the application of emerging technologies including punch cards and photography as well as the steadily expanding use of digital technologies. Working for SRI, he needed to know the state of the art of whatever problem he was addressing. In any case, it was his nature to want to be familiar with the landscape in which he was working. Affable, polite, and widely known as “Charlie,” his broad knowledge soon made him the “go to guy” and he was in demand as an instructor, as a speaker, and as consultant. He was retained for applied research and consultation by a very wide range of institutions both at home and abroad.

From early on Charlie demonstrated abilities to cope and excel in quite diverse ways. He worked on a steamboat, as a cook, picked fruit, and supported his college studies as a judo instructor. Competent, thorough, practical, and systematic are adjectives that spring to mind. His academic degrees in both electrical engineering and industrial engineering gave him an excellent grounding for his professional career.

Personal papers are often a disorganized, incomplete, and, in effect, an eclectic mess. The ideal is likely to result when the person involved has three characteristics: First, that person should retain a collection that, if not exhaustive, is at least comprehensive in its coverage. In other words, the papers retained should be relatively complete, which requires steering between gaps in coverage and the packrat mentality that result in collections that are exhaustive – and exhausting. Second, he or she should understand the topics covered in the papers and how the papers relate to the whole. The third requirement is that the papers be well organized. These qualities are not often found, but Charlie Bourne’s deposited papers are strong in all three aspects.

They are, therefore, as an archive of historical papers, a rich and most promising resource for future. But it is not merely a promise. The proof is already at hand because the historical value of Charles Bourne’s papers has already been very richly demonstrated since they formed the basis for the encyclopedic History of online information services, 1963-1976 that he co-authored with Trudi Bellardo Hahn (MIT Press, 2003). Thanks to the hospitality of the Computer History Museum the benefits derived from Charles Bourne’s career will continue permanently.

Berkeley, 2019