For five summer days in 1976, the first generation of computer rock stars had its own Woodstock. Coming from around the world, dozens of computing’s top engineers, scientists, and software pioneers got together to reflect upon the first 25 years of their discipline in the warm, sunny (and perhaps a bit unsettling) climes of the Los Alamos National Laboratories, birthplace of the atomic bomb.

After a multi-year recovery and restoration process, the Computer History Museum is delighted to announce it is making available 21 never-before-seen video recordings of this unique conference. You can watch them here.

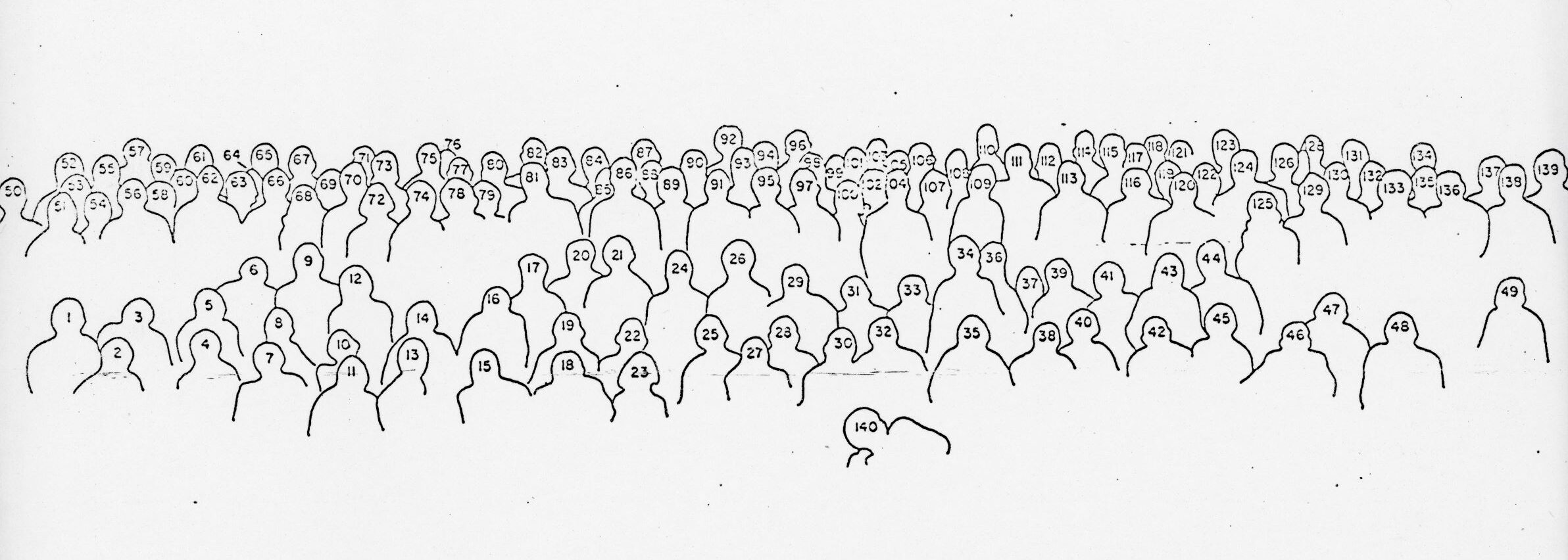

See the photo in its original size in a PDF here. Los Alamos Conference Attendees, Los Alamos, NM, 1976. https://www.computerhistory.org/collections/catalog/102695546

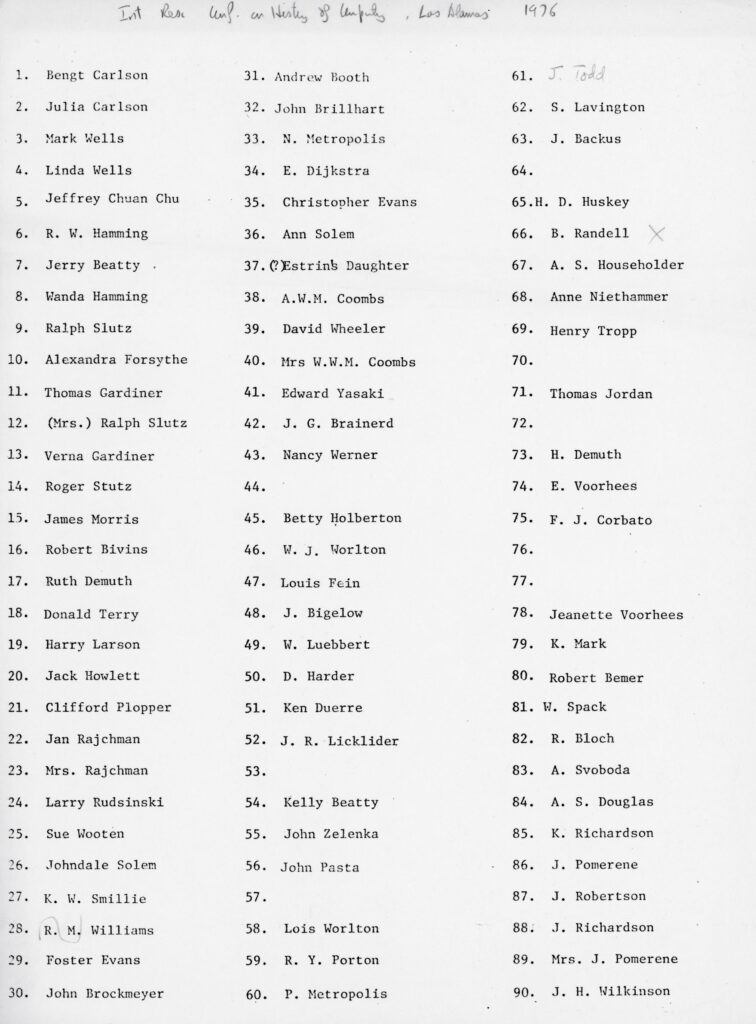

Legend for the Los Alamos Conference photo above, 1976.

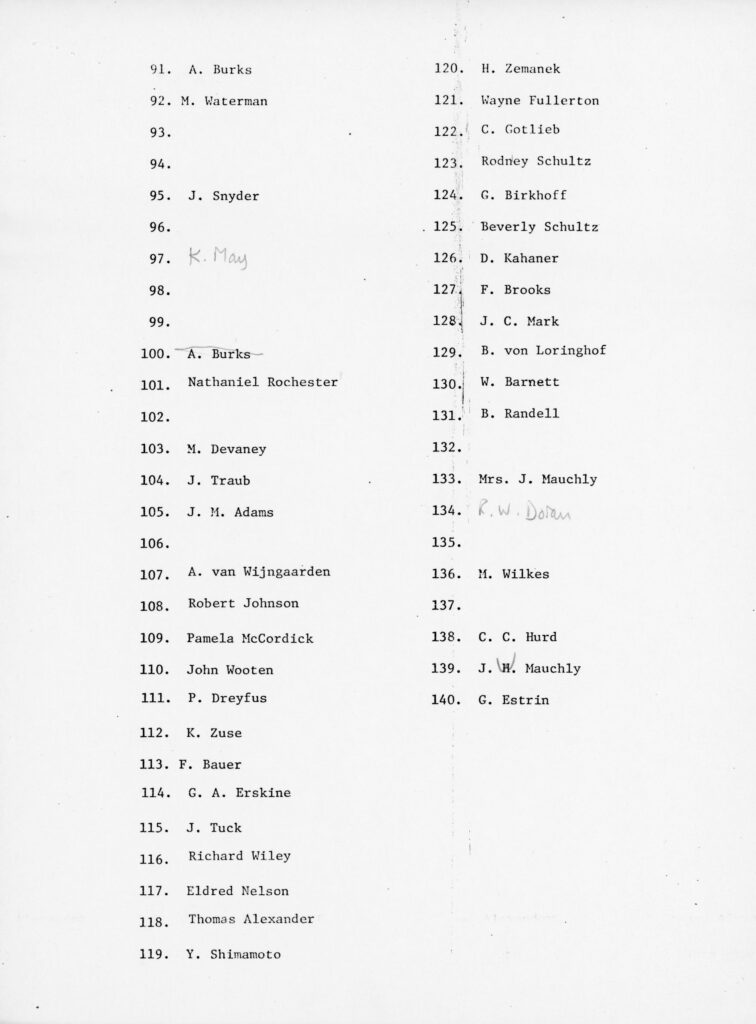

List for the Los Alamos Conference Legend, 1976.

Continuation of the list for the Los Alamos Conference Legend, 1976.

In its early years (1950s and ‘60s), computing was a field wide open for exploration. Since so much was new, innovators building computers in this period of early discovery often invented things of permanent, lasting value to computing—either in hardware or software. Engineer Bob Everett’s remarks on the legendary MIT Whirlwind computer describes MIT’s 1952 perfection of magnetic core memory—thereby solving the single biggest bottleneck facing early computer designers. (Before magnetic core memory, there was no reliable, electronic, digital, random-access memory for building computers with, retarding any further progress until solved).

MIT’s Bob Everett on Whirlwind’s magnetic core memory.

Conference speakers remembered these innovations, still in recent memory, leaving behind a one-of-a-kind record of why these early pioneers did what they did and why. Many of the machines in this first generation—17 of them were based upon the Institute for Advanced Study parallel binary architecture—were discussed at the conference: ENIAC, EDVAC, SEAC, SWAC, MANIAC, and ORACLE, among others. The remarkable thing these systems had in common was that they were essentially hand-built. The title of "programmer," "systems analyst," or other formal and now-familiar job titles did not exist: these machines were built by engineers, technicians, mechanics, and scientists for whom their often-finicky nature could be justified by the advanced calculations they performed. And nearly all of these early machines were "number crunchers"—designed for computation and solving advanced scientific and engineering problems. Setting the conference in Los Alamos was thus appropriate in a way, given the vast number of computations required in fulfilling the Labs’ wartime and later national security mission. Today, some of the most powerful supercomputers in the world are at the Labs.

Typical of computers of this generation, the 1946 ENIAC, the earliest American large-scale electronic computer, had to be left powered up 24 hours a day to keep its 18,000 vacuum tubes healthy. Turning them on and off, like a light bulb, shortened their life dramatically. ENIAC co-inventor John Mauchly discusses this serious issue.

Inventor John Mauchly discusses not turning off ENIAC.

Every concert has its high point… when Jimi Hendrix sets his guitar on fire or Pete Townshend shoves his guitar into a waiting amplifier. The Los Alamos peak moment was the brilliant lecture on the British WW II Colossus computing engines by computer scientist and historian of computing Brian Randell. Colossus machines were special-purpose computers used to decipher messages of the German High Command in WW II.

Based in southern England at Bletchley Park, these giant codebreaking machines regularly provided life-saving intelligence to the allies. Their existence was a closely-held secret during the war and for decades after. Randell’s lecture was—excuse me—a bombshell, one which prompted an immediate re-assessment of the entire history of computing. Observes conference attendee (and inventor of ASCII) IBM’s Bob Bemer, “On stage came Prof. Brian Randell, asking if anyone had ever wondered what Alan Turing had done during World War II? From there he went on to tell the story of Colossus—that day at Los Alamos was close to the first time the British Official Secrets Act had permitted any disclosures. I have heard the expression many times about jaws dropping, but I had really never seen it happen before.”

Brian Randell reveals secret World War II computer.

Publishing these original primary sources for the first time is part of CHM’s mission to not only preserve computing history but to make it come alive. We hope you will enjoy seeing and hearing from these early pioneers of computing. Leave us a comment below. We’d love to hear from you.

See all the videos on this playlist.

Blogs like these would not be possible without the generous support of people like you who care deeply about decoding technology. Please consider making a donation.